Turks and Caicos farm continues fishery enhancement work

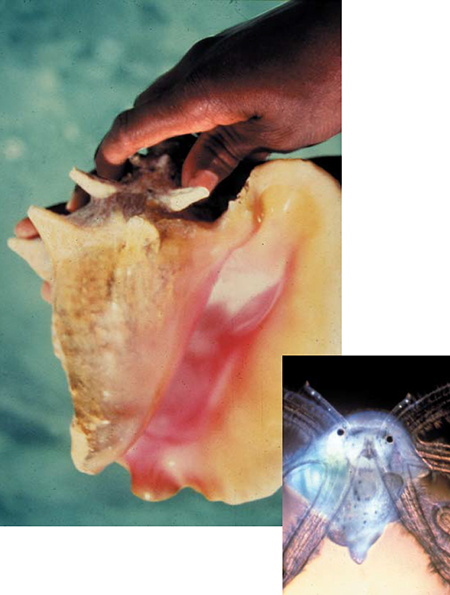

The queen conch (Strombus gigas) is a large marine gastropod that inhabits shallow seagrass beds of Florida, USA; the Bahamas; and the Caribbean. It has supported subsistence and commercial fisheries in these areas for centuries. Increased human populations throughout the range of the queen conch, the development of improved diving equipment, and strong export demand have all contributed to the overfishing of conch stocks in the last 30 years. Demand is strong due to the delicious meat and beautiful shell, prized by collectors.

Because it can take up to three years for a conch to reach market size, and hence replenish a fished-out area, demand is hard to meet unless overfishing is curtailed. The drastic decline in conch stocks throughout its range has promoted efforts to develop mariculture techniques to replenish and re-establish depleted conch populations.

This work began in the 1970s and continues today at the Caicos Conch Farm in the Turks and Caicos Islands, and through such programs as the conch project at the Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institution in Ft. Pierce, Florida, USA.

Basic culture methods

Egg mass collection

During the conch reproductive season, typically March to September, egg masses are collected in the field from spawning aggregations and transported to the laboratory. Successful captive breeding programs for other Strombus species (S. costatus, S. raninus, and S. alatus) not only show great promise for spawning queen conch in captivity, but also may be a method for year-round egg production.

Larviculture

The planktotrophic veligers develop from the two-lobe stage, to four lobes, and to six lobes in 18 to 40 days, depending on the Strombus species. Veligers are cultured in filtered UV water at a concentration of 20 to 50 larvae per liter. They are fed Isochrysis galbana to achieve a final cell count of 5,000 to 30,000 cells cells per milileter of culture water.

Veligers will not metamorphose spontaneously. Consequently, they are exposed for three to five hours to an inducer (hydrogen peroxide or an extract of the red algae Laurencia) when they show the morphological signs of metamorphic competence. Veligers metamorphose at 1.0 to 1.5 mm shell length (SL). Approximately 75 percent of the veligers achieve metamorphosis.

Grow-out

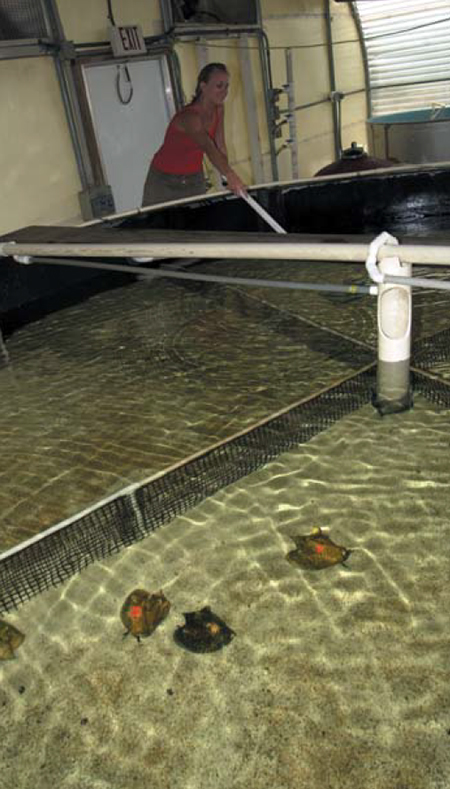

Postlarvae are stocked on screen trays at a density of 1,600 conch per square meter and fed a diet of flocculated Chaetoceros gracilis. Growth rates range between 0.2 and 0.3 millimeters per day, and survival is as high as 90 percent. Juvenile conch (5 mm SL) are stocked on sand trays and fed a mixture of flocculated Chaetoceros and artificial food. From 12 to 90 mm SL, the conch are placed in large circular ponds up to 15 m in diameter.

Optimal conditions for fast growth (0.3 millimeters per day) include rapid water flow, sand substrate, shaded area, and continuous supply of food. Under such conditions, survival continues to be 90 percent or greater. Food at this stage consists of pelleted diets and fresh algae (Ulva sp.) blended into a gel matrix. Final grow-out from 9 to 16 cm SL is typically accomplished in a fenced, undersea pasture. Time to grow-out can range from two months to three years, depending on the market.

Markets

The markets for farm-raised queen conch include the aquarium trade (2.5 cm SL), “ocean escargot” (6 cm SL), juveniles for restocking programs (7 to 9 cm SL) aimed at replenishing depleted populations in the wild or establishing new populations, and fullsized animals (16 to 18 cm SL).

A permit from the Convention of International Trade of Endangered Species (CITES) is needed for the trade of wild and cultured queen conch. This ensures that the species is harvested at a level consistent with its fisheries population. Research with non-restricted Strombus species (S. raninus and S. alatus) is currently underway to determine if they can serve as alternative species for the smallersized (2 to 6 cm SL) animal markets.

Conclusion

Fisheries management strategies and aquaculture programs throughout the Caribbean are helping to sustain and re-establish natural populations of queen conch. The development of techniques to mass rear and grow conch from egg to juvenile stages is an important component of these programs.

(Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the October 2000 print edition of the Global Aquaculture Advocate.)

Now that you've finished reading the article ...

… we hope you’ll consider supporting our mission to document the evolution of the global aquaculture industry and share our vast network of contributors’ expansive knowledge every week.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year. GSA individual and corporate members receive complimentary access to a series of GOAL virtual events beginning in April. Join now.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

-

Megan Davis, Ph.D.

Harbor Branch Oceanographic

Institution

5600 U.S. 1 North

Ft. Pierce, FL 34946 USA

Tagged With

Related Posts

Health & Welfare

Artificial diets for juvenile queen conch

Researchers found juvenile queen conch fed diets containing added macroalgae had higher survival than a control given catfish feed only.

Responsibility

In Delaware Bay, a delicate balancing act for shellfish farms

Oyster producers learn to adapt in a Delaware Bay ecosystem that's critical for endangered shorebirds and highly protected horseshoe crabs.

Intelligence

Bahamas venture focuses on grouper, other high-value marine fish

A new venture under development in the Bahamas will capitalize on Tropic Seafood’s established logistics and infrastructure to diversify its operations from processing and selling wild fisheries products to include the culture of grouper and other marine fish.

Intelligence

Queen conchs conservation through aquaculture, education

While queen conchs have supported ocean fisheries for centuries, declining populations and catches have prompted management measures and aquaculture development.