Green seaweed cultured in Mexico

In previous research, the authors have showed that the substitution of artificial feed binders with seaweed meal increased the water absorption of shrimp pellets and improved their texture while maintaining adequate pellet integrity. Shrimp-feeding results in the lab showed that a 2 to 4 percent inclusion of seaweed was cost-efficient, improved feed consumption, promoted faster growth, and had adequate attractant efficacy.

Green seaweed production

Commercial culture of the green seaweed Enteromorpha (recently renamed Ulva clathrata) began recently in Mexico. Previously, seaweed production was dominated by brown seaweeds like wild-harvested Macrocystis from Mexico, Ascophyllum, and Laminaria, and red seaweeds like Eucheuma produced in other countries. In the past, green seaweeds were confined to small niche markets because of their high costs of production, but using new technology, Enteromorpha can now be produced at a price competitive with other seaweeds.

Enteromorpha has several features that make it interesting as a potential ingredient in shrimp feed. It is highly regarded as a food item in Asia, with a reputation as a health food. It contains the sulfated polysaccharide ulvan, which can help in pellet binding and also has potential antiviral activity. Enteromorpha has two to three times higher protein content than other seaweeds and various vitamins and minerals. It is also an excellent source of carotenoids, which contribute to shrimp pigmentation.

Ingredient potential

The authors recently conducted research to assess the potential of Enteromorpha meal as an ingredient in commercial shrimp feed formulation. They compared the green seaweed Ulva clathrata with two kelp seaweeds commonly used in shrimp feed, Macrocystis and Ascophyllum. Standard pelleted test diets with 3.3 percent Macrocystis, Ascophyllum, or Enteromorpha were compared with respect to pellet stability and texture, shrimp growth performance, and shrimp pigmentation.

Enteromorpha has higher protein and carotenoid levels and approximately 30 percent lower hydrocolloid levels than those in Macrocystis and Ascophyllum. Instead of the mix of alginates and sulfated fucoidan typical of Macrocystis and Ascophyllum, Enteromorpha has only sulfated ulvan.

Results

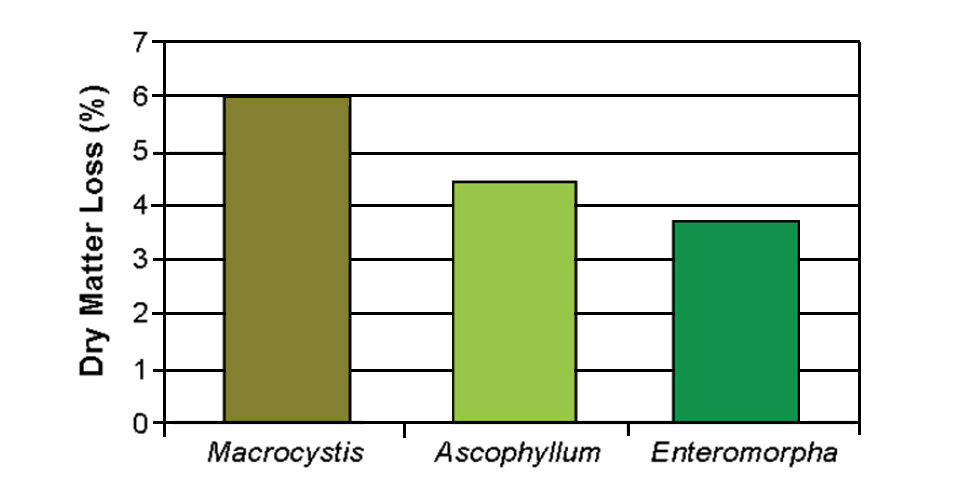

Despite its lower hydrocolloid levels, Enteromorpha had acceptable binding properties with significantly better retention of dry matter (Fig. 1) and superior water absorption. Increased water absorption results in a softer pellet that shrimp eat more readily than harder pellets.

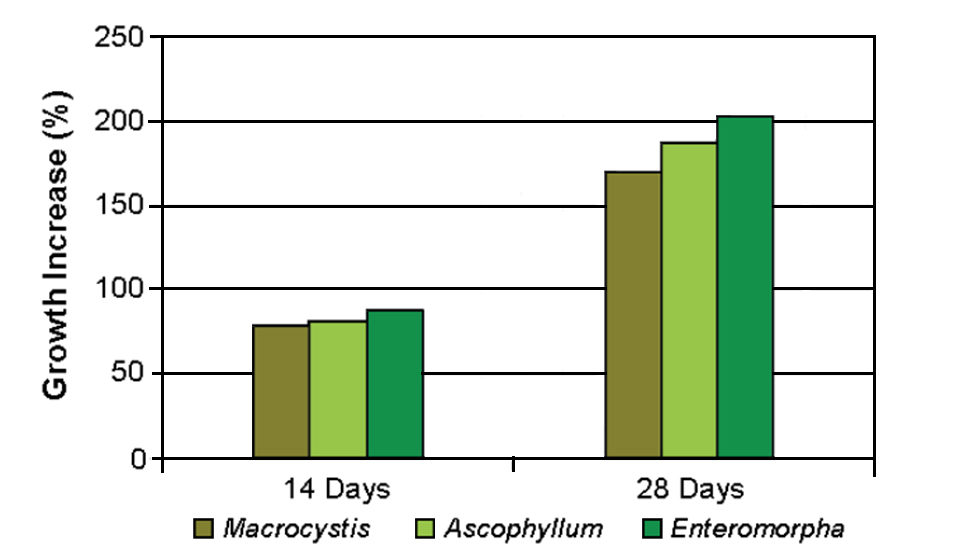

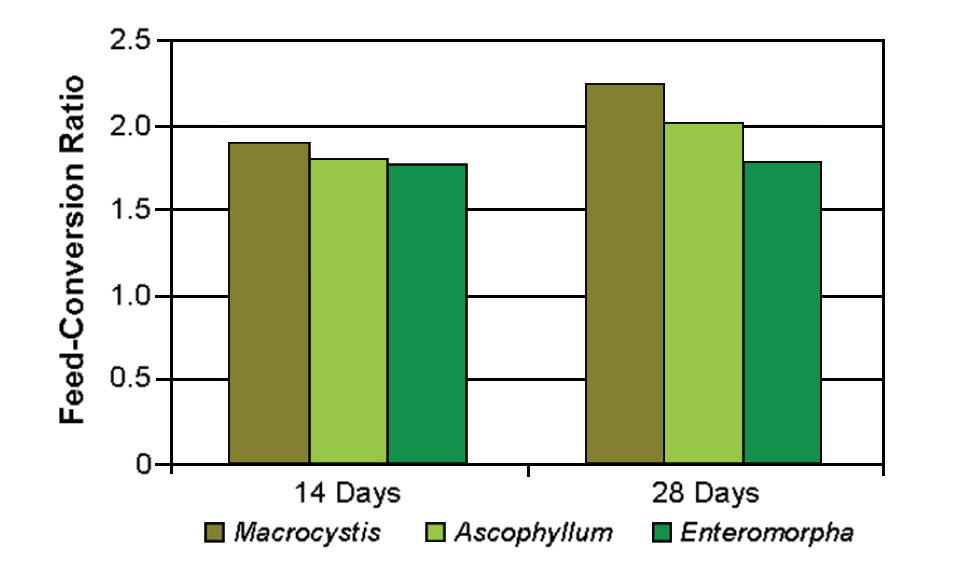

Growth of the (Litopenaeus vannamei) was greater in shrimp fed pellets containing Enteromorpha than those with Macrocystis or Ascophyllum (Fig. 2). Similarly, feed with Enteromorpha produced the best feed-conversion ratio (1.78 at 28 days) (Fig. 3), and its amino acid contribution was higher than that of Macrocystis or Ascophyllum.

Red coloration after cooking was markedly darker in animals fed the Enteromorpha diet due to the high carotenoid levels typical of Enteromorpha. Shrimp with greater pigmentation typically have better consumer appeal.

Of the three seaweeds tested, Enteromorpha had the best nutritional and functional properties as an ingredient in shrimp aquafeeds. Its possible antiviral and immunological properties will be the subject of further research.

(Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the November/December 2006 print edition of the Global Aquaculture Advocate.)

Now that you've finished reading the article ...

… we hope you’ll consider supporting our mission to document the evolution of the global aquaculture industry and share our vast network of contributors’ expansive knowledge every week.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year. GSA individual and corporate members receive complimentary access to a series of GOAL virtual events beginning in April. Join now.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Authors

-

Dr. L. Elizabeth Cruz-Suarez

Programa Maricultura

Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León

Cd. Universitaria F-56

San Nicolás de los Garza

Nuevo León 66450, México[120,109,46,108,110,97,117,46,98,99,102,64,122,117,114,99,117,108]

-

Dr. Martha G. Nieto-Lopez

Programa Maricultura

Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León

Cd. Universitaria F-56

San Nicolás de los Garza

Nuevo León 66450, México -

Biol. Perla Patricia Ruiz-Díaz

Programa Maricultura

Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León

Cd. Universitaria F-56

San Nicolás de los Garza

Nuevo León 66450, México -

QBP Claudio Guajardo-Barbosa

Programa Maricultura

Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León

Cd. Universitaria F-56

San Nicolás de los Garza

Nuevo León 66450, México -

M.C. David Villarreal-Cavazos

Programa Maricultura

Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León

Cd. Universitaria F-56

San Nicolás de los Garza

Nuevo León 66450, México -

Dr. Mireya Tapia-Salazar

Programa Maricultura

Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León

Cd. Universitaria F-56

San Nicolás de los Garza

Nuevo León 66450, México -

Dr. Denis Ricque-Marie

Programa Maricultura

Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León

Cd. Universitaria F-56

San Nicolás de los Garza

Nuevo León 66450, México

Tagged With

Related Posts

Health & Welfare

A case for better shrimp nutrition

Shrimp farm performance can often be below realistic production standards. Use proven nutrition, feeds and feeding techniques to improve profitability.

Responsibility

A helping hand to lend: UK aquaculture seeks to broaden its horizons

Aquaculture is an essential contributor to the world food security challenge, and every stakeholder has a role to play in the sector’s evolution, delegates were told at the recent Aquaculture’s Global Outlook: Embracing Internationality seminar in Edinburgh, Scotland.

Responsibility

Beefing up seaweed production to green up beef

Josh Goldman is on a mission to reproduce asparagopsis, a tropical seaweed that could have a significant impact on global greenhouse gas emissions.

Responsibility

Lean and green, what’s not to love about seaweed?

Grown for hundreds of years, seaweed (sugar kelp, specifically) is the fruit of a nascent U.S. aquaculture industry supplying chefs, home cooks and inspiring fresh and frozen food products.