Pathogen can threaten freshwater polyculture systems with various crustacean species

The giant freshwater prawn (Macrobrachium rosenbergii) – native to Malaysia, Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, Myanmar, Bangladesh, India, Sri Lanka and the Philippines, and introduced to many other countries – is a valuable crustacean species for aquaculture. It is generally considered to be less prone to some viral diseases under farming conditions when compared to penaeid shrimp, although various viral pathogens can affect it.

Recently reported new viruses for crustaceans include the red claw crayfish (Cherax quadricarinatus) iridovirus (CQIV) and the shrimp hemocyte iridescent virus (SHIV) from Pacific white shrimp (Penaeus vannamei). In March 2019, the Executive Committee of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) approved a proposal for a new species of Decapod Iridescent Virus 1 (DIV1) in the new genus Decapodiridovirus, to include SHIV and CQIV. To date, DIV1 has been detected in farmed Pacific white shrimp (Penaeus vannamei) and other penaeid species; in red claw crayfish; in red swamp crayfish (Procambarus clarkii); in oriental river prawn (Macrobrachium nipponense) and in M. rosenbergii in China, indicating that DIV1 poses a new threat to the shrimp farming industry.

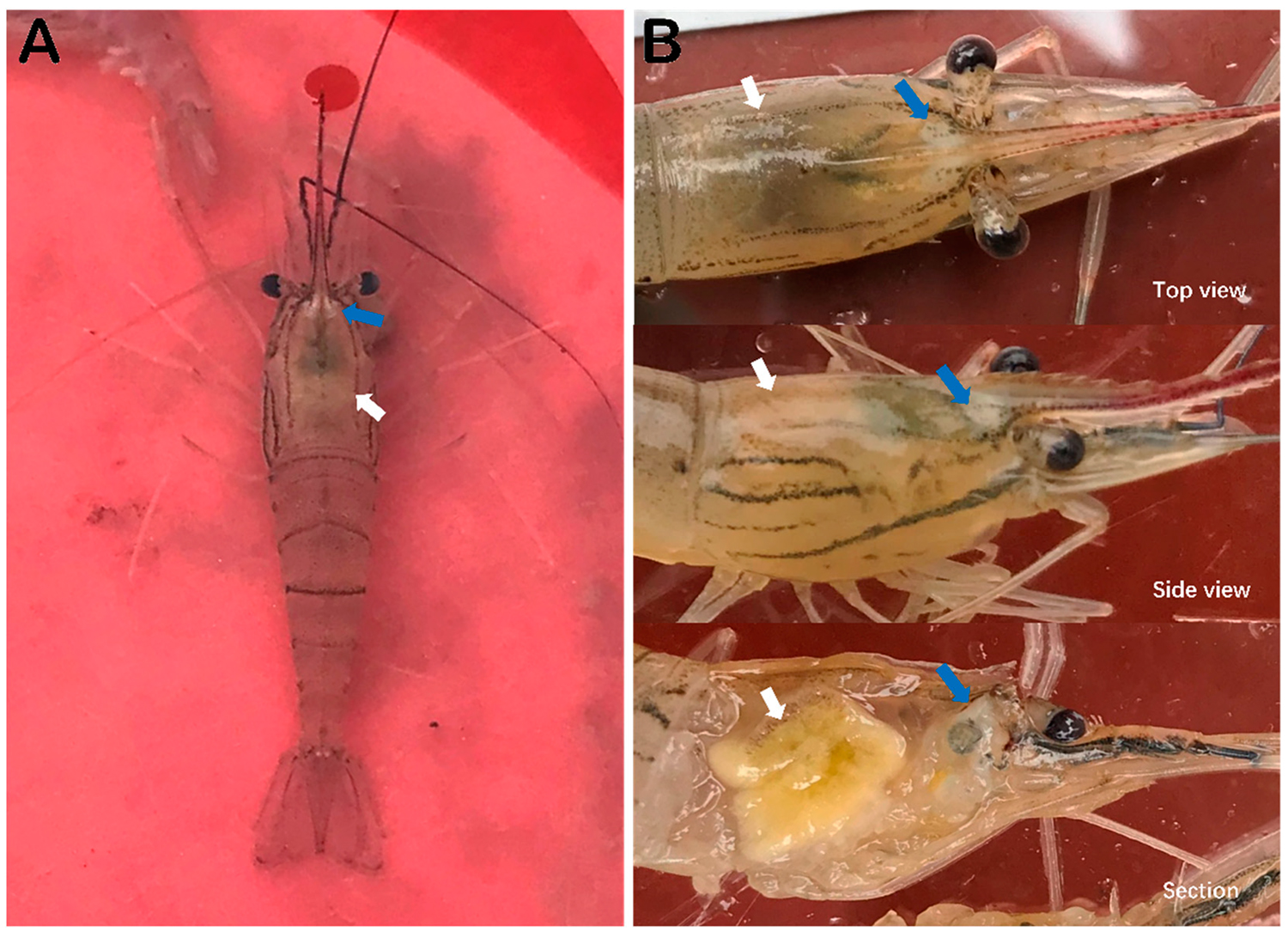

In recent years, a new disease reported in M. rosenbergii farms in China has been commonly called “white head” or “white spot,” because diseased prawns exhibit a typical white triangle under the carapace at the base of rostrum (head spine). It can have a cumulative mortality of up to 80 percent. It is noteworthy that many M. rosenbergii populations suffering from white head were being polycultured with P. vannamei.

This article – summarized and adapted from the original article (Qiu L., Chen X., Zhao R.H., Li C., Gao W., Zhang Q.L. and Huang J. 2019) – reports on a study of a diseased polyculture population of M. rosenbergii and red swamp crayfish, P. clarkii. Most of the M. rosenbergiiexhibited the typical white triangle and appeared moribund or had died. One month before we collected the samples for this study, all of the P. vannamei in an adjacent pond had died.

Study setup

Samples of farmed M. rosenbergii (4 to 6 cm long) and P. clarkii (5 to 7 cm long) were collected from a pond with high mortality in a farm in the eastern-central coastal Province of Jiangsu, People’s Republic of China. In the same pond, other wild crustaceans – including other prawn species and water fleas (cladocerans) – were also sampled for further analysis. Dead and dry bodies of P. vannamei (5 to 7 cm) were collected on the drained bottom of the adjacent pond, which suffered from a severe disease one month before.

The collected samples were subjected to several tests. For detailed information on sample collection; DNA and RNA extractions; pathogen detection; histopathological sections; isothermal amplification; transmission electron microscopy (TEM); and other moleculare techniques used, refer to the original publication.

Results and discussion

In this study we reported farmed M. rosenbergii and P. clarkii – cohabitating with other wild crustaceans – suffering a severe mortality following the death of an adjacent P. vannameipopulation. Real-time PCR results showed that all samples were negative for several shrimp viruses – including White Spot Syndrome Virus (WSSV), Infectious Hypodermal and Hematopoietic Necrosis Virus (IHHNV), Vibrio parahaemolyticus-Acute Hepatopancreatic Necrosis Disease (VpAHPND), Yellowhead Virus (YHV), Infectious Myonecrosis Virus (IMNV) and Covert Mortality Nodavirus (CMNV) – but were positive for DIV1.

Samples of M. rosenbergii contained the highest DIV1 loads, ranging from 3.16 × 108 to 9.83 × 108 copies/µg-DNA, which were higher than any other naturally infected species in this and earlier studies, indicating that the disease of M. rosenbergii in this case was caused by a severe infection with DIV1. Therefore, this is the first confirmation of the causative agent of “white head” symptoms in farmed M. rosenbergii. In addition, we also determined DIV1 to be a natural pathogen to P. clarkii and M. nipponense.

While collecting and processing the samples, it was observed that most of the collected M. rosenbergii prawns exhibited obvious clinical signs, including the distinct white triangle area under the carapace at the base of rostrum, hepatopancreatic atrophy with color fading and yellowing, empty stomachs and guts (Fig. 1), and some moribund prawns also had slightly whitish muscle and mutilated antenna.

The susceptibilities of M. rosenbergii, M. nipponense, P. vannamei and P. clarkii to infection by DIV1 and infection by WSSV are different. Many farms in the Provinces of Jiangsu, Guangdong, and Zhejiang in China, as well as in Southeast Asia and Africa, have stocked ponds in polyculture mode with M. rosenbergii and P. vannamei or P. monodon. Because M. rosenbergii has tolerance to WSSV infection, a polyculture production approach provides a profitable approach for farmers under the threat of WSSV. However, the emergence of DIV1 has broken down this approach and verified our earlier warning that polyculture with different species of crustaceans may bring risks for spread of diseases, an increase of susceptible species and the evolution of pathogens, based on our early surveillance on shrimp epidemiology.

M. rosenbergii and P. vannamei infected with DIV1 both exhibited hepatopancreatic atrophy with color fading on the surface and empty stomachs and guts. However, these symptoms are not distinctive and can also be caused by other diseases – like White Spot Syndrome Virus (WSSV), Taura Syndrome Virus (TSV) and Acute Hepatopancreatic Necrosis Disease, or AHPND – and the hepatopancreas color loss is similar to the clinical feature of AHPND. It is relevant noting that “white head” is a typical clinical sign for on-site diagnosis of M. rosenbergii infected with DIV1.

Perspectives

Results of all the tests conducted – including description of symptoms, detection of known pathogens, histopathological and cytopathological observation, and others – confirmed that the so called “white head” symptoms of M. rosenbergii are caused by DIV1 infection. Additionally, this study also provided evidence to report red swamp crayfish (Procambarus clarkii) and oriental river prawn (Macrobrachium nipponense) as susceptible species to DIV1.

The disease was likely transmitted from the adjacent pond stocked with P. vannamei, which had died out during the outbreak of infection with DIV1 due to lack of biosecurity in the farm management. Our results show how DIV1 can threaten freshwater polyculture systems using different species of crustaceans, a practice we discourage.

Now that you've finished reading the article ...

… we hope you’ll consider supporting our mission to document the evolution of the global aquaculture industry and share our vast network of contributors’ expansive knowledge every week.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year. GSA individual and corporate members receive complimentary access to a series of GOAL virtual events beginning in April. Join now.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Authors

-

Dr. Liang Qiu

Yellow Sea Fisheries Research Institute

Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences

Qingdao, China -

Dr. Xing Chen

Yellow Sea Fisheries Research Institute

Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences

Qingdao, China -

Dr. Ruo-Heng Zhao

Yellow Sea Fisheries Research Institute

Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences

Qingdao, China -

Dr. Chen Li

Yellow Sea Fisheries Research Institute

Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences

Qingdao, China -

Dr. Wen Gao

Yellow Sea Fisheries Research Institute

Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences

Qingdao, China -

Dr. Qing-Li Zhang

Yellow Sea Fisheries Research Institute

Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences

Qingdao, China -

Dr. Jie Huang

Corresponding author

Yellow Sea Fisheries Research Institute

Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences

Qingdao, China

Tagged With

Related Posts

Health & Welfare

Emerging disease: Shrimp Hemocyte Iridescent Virus (SHIV)

SHIV is a new Pacific white shrimp virus in the Iridoviridae family. Authors also developed an ISH assay and a nested PCR method for its specific detection.

Health & Welfare

Clinical case report: EMS/AHPND outbreak in Latin America

Behind the successful control of Early Mortality Syndrome (EMS), or Acute Hepatopancreatic Necrosis Disease (AHPND), in a Latin American shrimp nursery.

Health & Welfare

Alphavirus replicon particles potential method for WSSV vaccination of white shrimp

A study demonstrated that VP19 and VP28 white spot syndrome virus envelope proteins expressed by replicon particles provided protection against mortality due to WSSV in shrimp.

Health & Welfare

EHP a risk factor for other shrimp diseases

Laboratory challenges and a case-control study were used to determine the effects of EHP infection on two Vibrio diseases: acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease (AHPND) and septic hepatopancreatic necrosis (SHPN).