Vibrio P62, Bacillus P64 can be used as probiotics for L. vannamei

The use of probiotic bacteria and immunostimulants are two promising and controversial methods recently implemented for the prevention and management of infectious shrimp diseases. One of the main challenges in developing probiotic bacteria is using appropriate selection and colonization methods. Probiotics should not inhibit shrimp growth or induce resistance to the probiotics used.

Bacterial strains

A study isolated bacteria with both probiotic and immunostimulant capacity. The probiotic strains used in the study were isolated from wild, adult (Penaeus vannamei) shrimp collected at Manglaralto, Ecuador. Half of each shrimp was used for histological analysis, while the hepatopancreas (HP) was extracted for bacterial isolation.

Probiotic strains were selected for their in vitro inhibition properties against Vibrio harveyi (S2), following Ruiz et al. (1996). Of 80 strains isolated, three came from healthy shrimp and inhibited in vitro growth of S2. By phenotypic observation AFLPs and 16S RNA gene sequencing, two strains were identified as Vibrios and another as Bacillus.

Experimental setup

For the three experiments described below, animals were acclimated for 15 days, with continuous water exchange and aeration in the culture system. Seawater was filtered and UV-sterilized, with temperature maintained at 28 degrees-C. Shrimp were fed 50 percent protein, commercial pellets sterilized daily. The aquariums were inoculated using the logarithmic phase of each strain at 107 bacteria per milliliter per aquarium.

Colonization capacity of bacteria

To test the colonization capacity of the bacteria, the experimental design was completely randomized with five replicates of eight treatments, with 20 1-gram shrimp in each 50-liter aquarium. Vibrio P62, Vibrio P63 and Bacillus P64 bacteria were used, with one control without bacteria.

After acclimation, only one bacterial inoculation was applied. Done without water exchange, the exposure time was 24 hours. For the recovery isolation, pools of 10 HP were used in replicate and five 1/10 serial dilutions were performed. Colonization percentages were evaluated by counting the colony-forming units (CFU) per gram HP based on colony morphology and identifying the strains by arbitrarily primed polymerase chain reaction using three primers. The health condition of the shrimp was determined by histology.

Interaction against V. harveyi

In a test of competitive interaction against V. harveyi, the strains Vibrio P62, Vibrio P63 and Bacillus P64 were used, as well as a negative control and pathogen control. Stock density, shrimp weight, and inoculum dose were the same as in the first experiment. The strains were inoculated for three consecutive days.

After 20 hours of exposure, 50 percent of the water was exchanged. On the fourth day of the experiment, V. harveyi (S2) was inoculated at 107 CFU per milligram for 24 hours before restarting the water exchange. Interaction percentages were evaluated by counting the CFU per gram of HP in Lb agar (2 percent NaCl), differentiating strains on morphological characteristics by AP-PCR and monoclonal antibodies against S2.

Immune system stimulation

Vibrio P62 and Bacillus P64 were used in an evaluation of the bacteria as immune system stimulants, with the strain V. alginolyticus (Ili strain) as a probiotic control. Shrimp of 1.5 ± 0.2 grams were distributed 10 animals each in 50-liter aquariums and fed commercial pellets at 3 percent biomass twice daily for 25 days.

The inoculation took place every two days during 10 days with 50 percent water exchange after 20 hours of exposure. After inoculation, haemolymph was extracted from each shrimp in intermolt stage. The stimulating effects of the strains were evaluated using haemogram counts, quantification of reactive oxygen intermediates, measurement of phenoloxidase activity, antibacterial activity quantification, and measurement of plasma protein concentration. The results of these tests were used to calculate the immune index.

Results

Of the 80 strains isolated from the HP of wild shrimp, two fulfilled the conditions of originating from healthy shrimps, reaching colonization percentages above 50 percent, inhibiting the in vivo growth of V. harveyi, and not causing histological damage in inoculated shrimp at a concentration of 107 CFU per milliliter.

Competitive exclusion power

The colonization experiment demonstrated the capacity of the strains to enter the HP and their competitive exclusion power. This effect was remarkable for Vibrio P62 and Vibrio P63, with the total quantity of CFU per gram HP not significantly different from the control (p > 0.05), indicating the high capacity of both Vibrios to inhibit autochthonous bacteria or carry out competitive substitution. The mean bacterial count reached at these treatments was 4.2 x 104 ± 8.5 x 103 CFU per gram HP, but the colonization percentage reached by Vibrio P62 was 83 percent, demonstrating a stronger antibacterial effect than Vibrio P63.

In the case of shrimp inoculated with Bacillus P64, the total bacterial number was significantly higher – 5.3 x 104 ± 7.6 x 103 CFU per gram, HP. Although the 58 percent colonization reached by this strain was similar to the one reached by the Vibrio P63 (60 percent), P63 was more efficient in performing the competitive substitution of the autochthonous flora. No histological damage was registered in the inoculated shrimp after 12 hours.

Competitive interaction

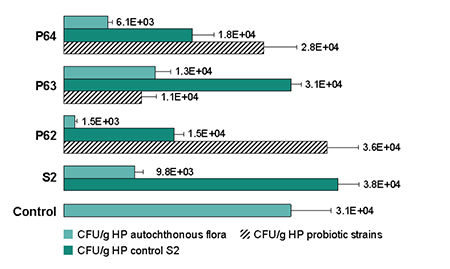

In the competitive interaction experiment, the total bacterial concentration increased by 64 percent with S2 inoculation, and up to 80 percent with the inclusion of probiotics. Vibrio P62 achieved the largest inhibitory effect, reducing by 60 percent the S2 penetration, while displacing the autochthonous microflora of the HP. The inhibitory effect of Vibrio P63 was greater on the natural flora than the pathogen S2, on which it achieved only 19 percent of inhibition. The Bacillus P64 inhibited the natural flora and competed with the pathogen, reducing by 34 percent the S2 penetration (Fig. 1).

Immune system stimulation

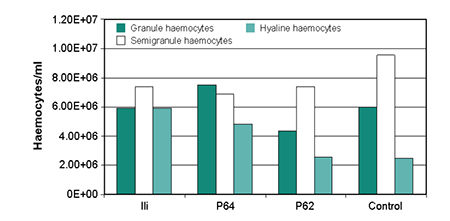

The total haemocyte count did not show significant differences between the treatments. The haemocyte population distribution was less in the shrimp inoculated with V. alginolyticus (Ili) and Bacillus P64 than in the control (Fig. 2). The phagocyte stimulation rate was low for all treatments, not registering significant differences (p > 0.05) of the reactive oxygen intermediate production (Table 1).

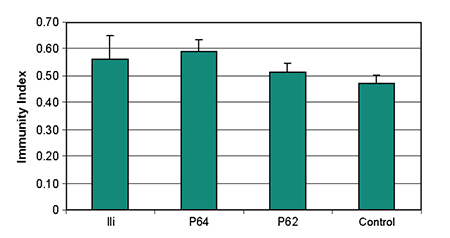

The phenoloxidase activity was significantly higher (p < 0.05) in shrimp stimulated with Bacillus P64, Vibrio P62, and V. alginolyticus (Ili). The antibacterial inhibition percentage of the plasma was lower than the control. The quantity of plasmatic proteins stayed within the normal range (Table 1). The global immune index was significantly greater (p < 0.05) in the shrimp stimulated with Bacillus P64 and V. alginolyticus (Fig. 3). Mean shrimp weights in the probiotic groups were significantly higher (p < 0.05) than the control.

Gullian, Mean immunological values of control and probiotic treatments, Table 1

| Immunitary Values | V. alginolyticus | Vibrio P62 | Bacillus P64 | Control |

|---|

Immunitary Values | V. alginolyticus | Vibrio P62 | Bacillus P64 | Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total haemocytes (cells/ml) | 2.2x7 ± 9.9x106 | 1.7x7 ± 4.9x106 | 2.1x7 ± 3.1x106 | 2.0x7 ± 3.9x106 |

| NBT rate | 1.18 ± 0.08 | 1.15 ± 0.11 | 1.20 ± 0.09 | 1.11 ± 0.05 |

| Antibacterial activity (%) | 8.5 ± 5.6 | 25.4 ± 13.7 | 20.6 ± 8.7 | 30.0 ± 9.0 |

| Plasmatic protein (mg/ml) | 112.1 ± 8.1 | 97.7 ± 6.0 | 102.6 ± 3.9 | 104.3 ± 8.6 |

| Phenoloxidase activity (O.D.) | 670 ± 0.02a | 661 ± 0.07a | 738 ± 0.08a | 449 ± 0.05b |

Conclusion

Results of this study demonstrated that the isolated beneficial bacteria of the natural microflora are potential competitors of pathogenic bacteria. The interaction of Vibrio P62 and Bacillus P64 with V. harveyi (S2) confirmed it is possible to diminish the colonization of this strain in the hepatopancreas.

The inoculation of Vibrio P62 and Bacillus P64 during 10 days improved the general health of the shrimp. The total number of haemocytes and total plasmatic protein concentrations in the three treatments remained within normal values, indicating the administration did not deteriorate shrimp health. However, the immune index evaluation showed Bacillus P64 and V. alginolyticus (Ili) were more effective than Vibrio P62 at stimulating the shrimp immune response.

Results demonstrated that Vibrio P62 and Bacillus P64 can be used as probiotics in the prevention of P. vannamei diseases. The main objective in their use would be to limit the appearance of pathogenic bacteria in culture ponds. We believe this occurs by competitive exclusion or by stimulation of a defense reaction in the host.

Note: Cited references are available from the authors.

(Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the December 2002 print edition of the Global Aquaculture Advocate.)

Now that you've finished reading the article ...

… we hope you’ll consider supporting our mission to document the evolution of the global aquaculture industry and share our vast network of contributors’ expansive knowledge every week.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year. GSA individual and corporate members receive complimentary access to a series of GOAL virtual events beginning in April. Join now.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Authors

-

Mariel Gullian, Ms.C.

Centro de Servicios para la Acuicutura

P.O. Box 09-01-4519

Guayaquil, Ecuador -

Jenny Rodríguez, Ph.D.

Fundación CENAIM-ESPOL

Guayaquil, Ecuador

Related Posts

Intelligence

Current production, challenges and the future of shrimp farming

At the Guatemalan Aquaculture Symposium in Antigua, the focus was shrimp farming in the region: production, nutrition, health management and markets.

Aquafeeds

Hydrolyzed fish: Alternative ingredient for aquafeeds

Hydrolyzed fish byproducts can serve as highly digestible feed ingredients with significant amounts of amino acids and fatty acids.

Health & Welfare

Nutrition and genes research at Virginia Tech

Transcriptomics studies highlight impacts of different treatments on specific genes that can be targeted via nutritional intervention to increase farmed animal performance or welfare.

Health & Welfare

Use of probiotics in shellfish aquaculture

A review of the application of probiotics in shellfish aquaculture, methods of administration, mode of actions and their enhancing effects.