An overview of micronutrient requirements of broodstock and juveniles

The Japanese eel (Anguilla japonica) is an important and valuable food fish in East Asia, and an important cultured aquatic species because of its high market value and demand, desirable taste and supply shortages. They are grown in aquaculture ponds in several countries, including Japan, China and the Republic of Korea, and are an important component of the food culture.

Unfortunately, according to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN), this species has been put on notice under the Endangered Red List. There are various reasons related to natural stock declines of the Japanese eel, such as widespread habitat modifications, environmental pollution and overexploitation of wild stocks.

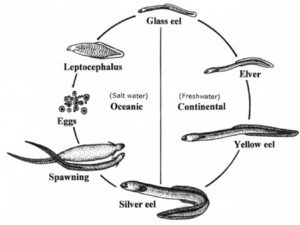

Eel aquaculture in Southeast Asia is highly dependent on wild-caught juveniles, which are eel larvae that, as they approach the coast, transform into miniature transparent eels called “glass eels.” Glass eels are actively caught and traded because of their high prices, and predictable seasonal migrations make them easy to catch. This significantly affects the population abundance of this valuable fish. Additional research is still required to better understand the biology and life cycle of the Japanese eel, as well as its nutritional requirements.

Complex life cycle

The Japanese eel, Anguilla japonica, is one of the 16 species belonging to the Anguilla genus of freshwater eels. The life cycle of this catadromous (the life cycle of some fishes that spawn in the sea and the developing larval and juvenile stages migrate to fresh water to grow to adult size) fish species has been a mystery to scientists since ancient times, because it was impossible to track down egg or larvae in their natural habitats like rivers or coastal areas.

Mature Japanese eels undergo long spawning migrations over thousands of kilometers, from various, inland water bodies to the ocean. Their feeding behavior as carnivorous predators is based on small fish, insects and crustaceans; but during their long, spawning migrations, the mature eels stop feeding.

They spawn west of the Mariana Islands in the western North Pacific, within the North Equatorial Current. Adults die after spawning, and the developing larvae, called leptocephali (which means “slim head”), are transported westward by the North Equatorial Current and then northward by the Kuroshio Current to eastern Asia. There, they eventually develop into translucent glass eels, as they migrate in schools into freshwater habitats and eventually complete their development, inhabiting rivers, lakes, and estuaries in Japan, China, Taiwan, Korea, Vietnam and the northern Philippines.

Progress in eel breeding

Recent decades have seen a slow but steady progress in the controlled breeding of Japanese eels. In 1974, Japanese scientists were successful in obtaining larvae from eggs through hormone injections of broodstock animals; in 1976, they successfully maintained newly hatched eels for about two weeks; and in 2000, they announced the first production of glass eels. More recently, the production of glass eels in Japan has progressed to the successful rearing of thousands of glass eels per year, although the process is not yet cost-effective, but research continues.

In the Republic of Korea (ROK), the National Research Foundation (NRF) approved the first national project on artificial breeding of A. japonica in 2002. This research was carried out by the Feeds and Foods Nutrition Research Center (FFNRC) at Pukyong National University, Busan, Republic of Korea. In 2003, the FFNRC successfully produced fertilized eggs from induced, matured broodstock Japanese eels. This research continued and resulted in the successful hatching of Japanese glass eels in 2012. The ROK’s National Institute of Fisheries Science (NIFS) successfully reared and produced 100,000 F2 (second generation) eel larvae in 2015. Research work continues, to overcome the remaining bottlenecks for artificial reproduction of the species.

Challenging issues remain for the successful artificial production of Japanese eels including broodstock management, reducing the significant mortality during larval rearing, larval deformities and the lack of knowledge on nutritional requirements for the different life stages.

Continued research to improve artificial reproduction technology and larval rearing systems are critical objectives. Also, a better understanding and evaluation of the nutritional requirements of the life stages of Japanese eel, and the development of artificial feeds for larvae, juvenile and broodstock is highly required.

Progress in nutrition of eels

Research at the FFNRC has made significant contributions to the understanding of micronutrient requirements of juvenile and broodstock Japanese eel, including studies conducted on requirements for important nutrients like ascorbic acid, α-tocopherol, arachidonic acid and other fatty acids.

Bai, Eels, Table 1

| Juvenile (15 g) Nutrient | Juvenile (15 g) Source | Juvenile (15 g) Actual level (mg/kg or percent diet) |

|---|

Juvenile (15 g) Nutrient | Juvenile (15 g) Source | Juvenile (15 g) Actual level (mg/kg or percent diet) |

|---|---|---|

| Ascorbic acid | L-ascorbyl-2-monophosphate | 0, 24, 52, 108, 1137 |

| α-tocopherol | DL-α-tocopheryl acetate | 1, 17, 32, 62, 119 |

| Fatty acid | LA(n-6) : LNA(n-3) | 0.5:0.5, 0.33:0.66, 0.25:0.75(total 1%) |

| Fatty acid | ARA(n-6) : DHA+EPA(n-3) | 0.25:0.75, 0.5:0.5, 0.75:0.25(total 1%) |

| Arachidonic acid | Arachidonic acid | 0.07, 0.22, 0.43, 0.57, 0.78, 1.23(%) |

| Broodstock (360 g) Nutrient | Broodstock (360 g) Source | Broodstock (360 g) Actual level (mg/kg or percent diet) |

| Ascorbic acid | L-ascorbyl-2-monophosphate | 32, 206, 423, 840, 1686 |

| α-tocopherol | DL-α-tocopheryl acetate | 72, 102, 158, 212, 398 |

| Arachidonic acid | 40% Arachidonic acid | 0, 0.33, 0.71, 1.06, 1.65(%) |

Ascorbic acid (Vitamin C) is a water-soluble vitamin that is involved in many enzymatic actions. It is essential for cartilage and collagen formation and significantly important for reproduction, growth, wound healing and resistance to stress; it is also an effective, water-soluble antioxidant. Vitamin E, or α-tocopherol, is a fat-soluble vitamin and a strong antioxidant that scavenges free radicals, and has a vital physiological role along with Vitamin C and selenium. It is found in most tissues and cell membranes and has an important function in the reproduction cycle.

Bai, Eels, Table 2

| Juvenile (15 g) Nutrient | Juvenile (15 g) Requirement (mg/kg or percent diet) | Juvenile (15 g) Response Criteria |

|---|

Juvenile (15 g) Nutrient | Juvenile (15 g) Requirement (mg/kg or percent diet) | Juvenile (15 g) Response Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Vitamin C | 41.1 ~ 43.9 | WG, FE |

| Vitamin E | 21.2 ~ 21.6 | WG, FE |

| Essential fatty acids | LA : LNA 1% (in 0.5:0.5 or 0.33:0.66) | WG, FE |

| Broodstock (360 g) Nutrient | Broodstock (360 g) Requirement | Broodstock (360 g) Response Criteria |

| Vitamin C | 410.7 ~ 911.7 | Liver/testes AA concentrations |

| Vitamin E | 212.9 ~ 199.7 | Liver/testes α-Toc concentrations |

| Arachidonic acid | 0.71 ~ 0.92 % | WG |

In addition, the amount and type of lipids in their diet are very important for carnivorous fish like Japanese eels, because they utilize poorly the carbohydrates in their diets as an energy source, and thus mostly depend on lipids. Having optimum levels of dietary lipids can positively influence protein utilization in fish, and the essential fatty acid requirements of Japanese eels appear to be somewhat similar to those of rainbow trout and common carp.

Perspectives

There are still many research and knowledge gaps in the domestication, controlled breeding and nutritional requirements of the Japanese eel. In particular, the elucidation of the nutritional requirements of Japanese eels at different stages of their life cycle. The controlled, cost-effective production of healthy glass eels at adequate survival rates are fundamental requirements to support further development of the eel aquaculture industry.

Now that you've finished reading the article ...

… we hope you’ll consider supporting our mission to document the evolution of the global aquaculture industry and share our vast network of contributors’ expansive knowledge every week.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year. GSA individual and corporate members receive complimentary access to a series of GOAL virtual events beginning in April. Join now.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Authors

-

Sungchul C. Bai, Ph.D.

Department of Marine Bio-materials and Aquaculture/Feeds and Foods Nutrition Research Center

Pukyong National University

Busan 608-737, Korea -

Ali Hamidoghli

Department of Marine Bio-materials and Aquaculture/Feeds and Foods Nutrition Research Center

Pukyong National University

Busan 608-737, Korea

Tagged With

Related Posts

Innovation & Investment

Maine scallop farmers get the hang of Japanese technique

Thanks in part to a unique “sister state” relationship that Maine shares with Aomori Prefecture, a scallop farming technique and related equipment developed in Japan are headed to the United States. Using the equipment could save growers time and money and could signal the birth of a new industry.

Aquafeeds

A look at protease enzymes in crustacean nutrition

Food digestion involves digestive enzymes to break down polymeric macromolecules and facilitate nutrient absorption. Enzyme supplementation in aquafeeds is a major alternative to improve feed quality and nutrient digestibility, gut health, compensate digestive enzymes when needed, and may also improve immune responses.

Health & Welfare

Aiding gut health with a natural growth promotor

A study with Nile tilapia conducted in commercial production cages in Brazil showed the potential – in the absence of major disease threats – of a commercial, natural growth promotor that modulates the microbiota (inhibiting growth of pathogenic bacteria and promoting growth of beneficial bacteria) and inhibits quorum sensing.

Health & Welfare

Aquamimicry: A revolutionary concept for shrimp farming

Aquamimicry simulates natural, estuarine production conditions by creating zooplankton blooms as supplemental nutrition to the cultured shrimp, and beneficial bacteria to maintain water quality. Better-quality shrimp can be produced at lower cost and in a more sustainable manner.