Work conducted at Charoen Pokphand Bahari farm in South Sumatra

The Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) is the most popular farmed shrimp species in the Western Hemisphere. It is now also commercially cultured in several countries in Asia, although only China appears to be producing significant quantities.

Culture of the species began recently in Thailand using specific pathogen-free (SPF) postlarvae (PL). L. vannamei were introduced in Indonesia in 2000 and initially cultured in East Java. SPF PL are currently used by several farms in Indonesia.

Status in Indonesia

Ten or so L. vannamei hatcheries in Situbondo and Banyuwangi, East Java, can produce approximately 150 million PL per cycle. These PL are used by local farmers or sent to farms in Lampung, South Sumatra; Balikpapan and Tarakan, Kalimantan; and Ujungpandang, Sulawesi.

Successful pond grow-out has produced yields of 7 to 10 metric tons (MT) per hectare, with animals reaching 15 grams in 90 days. Survival rates of 75 to 90 percent and 1.1 to 1.4:1 feed conversion ratios have been reported. Indonesia could produce 5,000 MT of cultured L. vannamei in 2002, and possibly reach 20,000 MT in 2003.

Viral disease

East Java may have had some viral problems recently. Eighty percent of the farms in Situbondo and Probolingo experienced major losses in ponds stocked in July 2002. The gross signs observed in affected shrimp included white spots on carapaces and reddish-colored bodies – later confirmed as White Spot Syndrome Virus (WSSV) by the Brackishwater Aquaculture Development Center laboratory in Jepara.

WSSV could have been transmitted from the broodstock or affected weaker, less-resistant shrimp during pond culture. However, samples tested were negative for Taura Syndrome Virus. At farms that were not as affected, shrimp growth – animals required 100 to 105 days to reach 15 grams.

Most of these affected farms were stocked with PL produced from pond-reared broodstock that could not have been SPF. Most of these broodstock were suspected positive for Infectious Hypodermal and Haematopoietic Necrosis Virus (IHHNV).

Integrated operation provides SPF PL

The Charoen Pokphand Bahari (CPB) shrimp project on the northern coast of South Sumatra, Indonesia is well integrated, with a hatchery, feed mill, power plant and processing and cold storage facilities. The CPB hatchery in Lampung has been producing about 100 million PL per month from SPF L. vannamei broodstock imported from Hawaii, USA. The SPF PL are utilized at the C.P. Bahari farm and also distributed to farms in other areas of Indonesia.

The farm is operated under the so-called “plasma” profit-sharing system, where each credited family operates an intensive 0.5-ha pond with management assistance from Charoen Pokphand Bahari. In this team approach, the credited farmer is the plasma and CPB, the nucleus, supplies PL, feed and electricity, and buys back the shrimp produced by the farmers.

The farm has over 3,100 family ponds and 300 company ponds. Technical support is provided by CPB’s central laboratory and research facilities at the farm site. Currently, the black tiger shrimp (Penaeus monodon) is the main species produced, but commercial production of L. vannamei began in mid-2002 at the farm.

L. vannamei trials

Locally available L. vannamei PL from East Java were used for initial trials in mid-2001. In subsequent trials, CPB PL from SPF broodstock were stocked. The PL10 (about 8.0 mm long) postlarvae were evaluated for developmental stage and size, presence of Vibrio spp., necrosis and gill development, and subjected to a stress test.

Biosecurity

As a biosecurity measure, ponds were fenced with plastic barriers to keep potential pathogen carriers like crabs out. Twined nylon lines with attached plastic strips were also placed over the ponds at every 2 meters to discourage flying birds from entering the pond area. Intake pipes were fitted with filter net bags to prevent the entry of water-borne pathogen carriers. Existing carriers were eradicated in reservoirs and production ponds before stocking.

Culture system and management

An open-flow system was used with treated water from reservoirs pumped into the main supply canal. From there, the water was distributed to production ponds. During culture operations, concentrated waste was discharged or siphoned into a wastewater canal.

The farm had three types of production ponds: HDPE-lined, partially lined, and with earthen bottoms. Modules included common quarantine and treatment reservoirs that supplied a set of production ponds. A module consisted of 40-60 ponds with four or five reservoirs with an area equivalent to 20 percent of the production ponds. Aeration of 10 horsepower per pond included eight paddlewheels placed to create currents to move organic waste and sludge toward the center drains of the ponds. Water exchange was minimal initially, but progressively increased to 10 percent daily as needed. Bottom siphoning was done twice every week or as required.

The modules were initially designed to function as recirculation systems with a clean water canal from the production ponds leading back to the reservoirs. After eradication of carriers at reservoirs and production ponds, the water was fertilized with urea and triple super phosphate to promote primary productivity. Products routinely used during pond preparation and operation included liming compounds and two probiotics.

Trial results

Temperature, salinity, pH and other pond water quality parameters were within acceptable ranges during the trials. The results summarized in Table 1 show progressive improvements in productivity from 3,634 to 10,094 kg shrimp per hectare. Survival and feed conversion also improved significantly.

Taw, L. vannamei performance in production trials, Table 1

| Trial 1 Nov. '01- March '02 | Trial 2 Dec. '01- May '02 | Trial 3 Feb. '02- July '02 | Trial 4 March '02- Aug '02 |

|---|

Trial 1 Nov. '01- March '02 | Trial 2 Dec. '01- May '02 | Trial 3 Feb. '02- July '02 | Trial 4 March '02- Aug '02 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of ponds | 10 | 10 | 11 | 14 |

| PL source | East Java | CPB | CPB | CPB |

| Pond type | Earthen | Earthen | HDPE/Earthen | HDPE |

| Stocking density (animals/m2) | 69 | 82 | 71 | 62 |

| Culture period (days) | 128 | 117 | 126 | 114 |

| Survival rate (%) | 29.5 | 74.1 | 92.1 | 93.3 |

| Average weight (g) | 15.10 | 13.15 | 15.23 | 17.66 |

| Feed-conversion ratio | 2.43 | 1.65 | 1.36 | 1.31 |

| Average daily gain (g) | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.16 |

| Productivity (kg/ha) | 3,634 | 7,946 | 9,933 | 10,094 |

| Productivity (kg/hp) | 182 | 397 | 497 | 475 |

Deformities

The high incidence (up to 46.5 percent) of deformities including deformed rostra, wrinkled antennal flagella, and cuticular roughness observed in harvested samples during the first trial was probably caused by stocking IHHNV-infected PL from East Java. This also probably contributed to the low productivity and high FCR for this trial. In subsequent trials with SPF PL, no deformities were observed.

Stocking density study

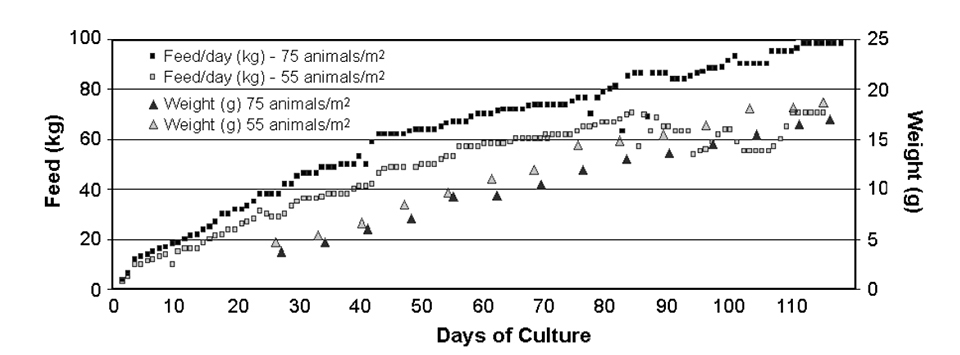

A four-month study on feed consumption and growth at stocking densities of 55 and 75 PL per square meter was also carried out. As expected, the higher density resulted in higher production and smaller shrimp sizes (Fig. 1).

The test system using HDPE-lined ponds averaged 475 kg shrimp per horsepower of paddlewheel aeration, and a maximum of 580 kilograms per horsepower was achieved. For comparison, McIntosh (2000) reported pond yields greater than 13,500 kilograms per hectare (550 kg shrimp per horsepower of paddlewheel aeration) at Belize Aquaculture Ltd. in Belize using zero water-exchange systems.

Protein requirements

An examination of protein content in feed used two shrimp diets produced at the C.P. Bahari feed mill: 38 to 40 percent protein feed normally used for P. monodon grow-out and a 30 to 32 percent protein aquafeed specially formulated for L. vannamei. The results (Table 2) confirmed that somewhat lower protein levels in feed had no effect on L. vannamei production performance. Production and efficiency were similar with both feeds, but production costs using lower-protein feeds are lower.

Taw, Results of feeding trials in ponds with L. vannamei, Table 2

| Parameter | Feed: 38-40% Protein | Feed: 30-32% Protein |

|---|

Parameter | Feed: 38-40% Protein | Feed: 30-32% Protein |

|---|---|---|

| Number of ponds | 3 | 3 |

| Area (m2) | 1,740 | 1,740 |

| Pond type | HDPE | HDPE |

| Stocking density (animals/mm2) | 60 | 60 |

| Initial average body weight (g) of nursery PL | 0.14 | 0.14 |

| Starting date | April 25, 2002 | April 25, 2002 |

| Harvest date | August 6-15, 2002 | August 6-16, 2002 |

| Days of culture | 108 | 107 |

| Final body weight (g) | 16 | 17 |

| Feed-conversion ratio | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| Survival rate (%) | 94 | 99 |

| Average daily gain (g) | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| Productivity (kg/ha) | 9,323 | 9,945 |

| Productivity/power input (kg/hp) | 424 | 431 |

Performance comparison: L. vannamei, P. monodon

In Indonesia, the culture of P. monodon is well established and the culture of L. vannamei is still very recent. However, information in Table 3, which shows the comparative performance of the two species, indicates that culture of L. vannamei is technically feasible and can be implemented in ponds originally built for P. monodon.

Taw, Performance comparison of L. vannamei and P. monodon, Table 3

| Parameter | L. vannamei Trial March ’02-Aug. ’02 | P. monodon March ’02-July ’02 |

|---|

Parameter | L. vannamei Trial March ’02-Aug. ’02 | P. monodon March ’02-July ’02 |

|---|---|---|

| Number of ponds | 14 | 10 |

| PL source | CPB | CPB |

| Pond type | HDPE | HDPE |

| Stocking density (animals/m2) | 62 | 37 |

| Days of culture | 114 | 120 |

| Survival rate (%) | 93.3 | 48.1 |

| Weight (g) at harvest | 17.66 | 23.29 |

| Feed-conversion ratio | 1.31 | 1.98 |

| Average daily gain (g/day) | 0.16 | 0.19 |

| Productivity (kg/ha) | 10,094 | 4,184 |

| Productivity (kg/hp) | 475 | 209 |

Note: Cited references are available from the first author.

(Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the December 2002 print edition of the Global Aquaculture Advocate.)

Now that you've finished reading the article ...

… we hope you’ll consider supporting our mission to document the evolution of the global aquaculture industry and share our vast network of contributors’ expansive knowledge every week.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year. GSA individual and corporate members receive complimentary access to a series of GOAL virtual events beginning in April. Join now.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Authors

-

Nyan Taw, Ph.D.

Senior Technical Advisor/Vice President

PT. Centralpertiwi Bahari

Charoen Pokphand Group

Lampung, Indonesia -

Sarayut Srisombat

General Manager, Research & Development

PT. Centralpertiwi Bahari

Charoen Pokphand Group

Lampung, Indonesia -

Saenphon Chandaeng

Manager, Company Ponds

PT. Centralpertiwi Bahari

Charoen Pokphand Group

Lampung, Indonesia

Related Posts

Responsibility

A look at various intensive shrimp farming systems in Asia

The impact of diseases led some Asian shrimp farming countries to develop biofloc and recirculation aquaculture system (RAS) production technologies. Treating incoming water for culture operations and wastewater treatment are biosecurity measures for disease prevention and control.

Health & Welfare

Biosecurity for shrimp farms

With the global spread of viruses, biosecurity has become an essential element of every shrimp farm. Biosecurity starts with quality of farm design.

Responsibility

Shrimp farming in Indonesia

In Indonesia, shrimp farming practices vary somewhat from region to region depending on the local conditions and financial pressures.

Responsibility

Malaysia shrimp farm redesign successfully combines biosecurity, biofloc technology

Blue Archipelago’s re-engineering of a large shrimp farm to a modular, biosecure facility set a benchmark for future shrimp culture projects in Malaysia.