Results show that fish stocking density affects yields

Aquaponics (AP), the integrated multi-trophic production of fish and plants in a semi-closed synergetic recirculating system, is one of the newest sustainable systems of food production. In AP systems, the biological wastes excreted by fish (e.g., ammonia, salts) and those generated from the microbial breakdown of feed for fish (i.e., nitrite and nitrate) are absorbed by plants as nutrients for growth. Thus, this method allows the removal of undesirable nutrient wastes from the water by plants and the reuse of the water for fish production. AP has been classified as one of the “10 technologies which could change our lives” by the European Union (EU) Parliament.

Although AP is based on a simple concept, i.e., the use of waste from fish as nutrients for the production of vegetables, its components can vary with different dimensional ratio forming a complete ecosystem that includes three major groups of organisms: fish, plants and bacteria. To our knowledge, little information is available about AP systems based on low technology, where the load of fish and consequently the water quality can heavily influence both the health of fish and the yield of vegetables.

This article – adapted and summarized from the original publication – evaluated the effect of rearing European carp (Cyprinus carpio L.) at two stocking densities on the water quality; fish growth; and the yield of three leafy vegetables: catalogna (Cichorium intybus), lettuce (Lactuca sativa), and Swiss chard (Beta vulgaris) in an AP system with low-technology, and compared it with a hydroponic cultivation.

Study setup

The experimental system was located inside a plastic greenhouse that was 50 percent shaded at the experimental farm of the University of Padova, in northeast Italy. The system had nine independent units divided as follows: three hydroponic units (HP), three AP units with low stocking density of fish (APL), and three AP units with high stocking density (APH). The AP units were designed as “low-technology systems” because they were characterized by: 1) the simplest hydroponic section with the capacity to act as biofilter; 2) the absence of energy to regulate water temperature; 3) the absence of probes for the continuous evaluation of water quality; 4) the absence of probes and systems for remote management; and 5) the absence of devices for water sanitation (UV, ozone).

The tanks were stocked with European carp (initial weight 169 grams ± 56 grams) from a commercial farm at stocking densities of 2.5 and 4.6 kg per cubic meter for the APL and APH treatments, respectively. The lower stocking density was chosen based on the minimum density capable of providing sufficient nitrogen for the growth of plants. The higher stocking density was selected to maintain the final biomass of fish (estimated as 3 to 3.5 times the initial weight) and below the maximum accepted for organic aquaculture (i.e., 15 kg per cubic meter). The fish were manually fed once a day with a commercial extruded pellet diet.

During the entire trial, the tanks for vegetables were cultivated in succession with catalogna chicory (Cichorium intybus, nine plants per square meter), lettuce (Lactuca sativa, 12 plants per square meter) and Swiss chard (Beta vulgaris, 10 plants per square meter), transplanted at the third true leaf stage. No pesticides or antibiotics in water or feed were used during the entire experiment.

For detailed information on the experimental setup; management of fish and vegetables; monitoring of fish, plants and water quality; and statistical analyses, refer to the original publication.

Results and discussion

The AP daily consumption of water due to evapotranspiration was not different among treatments, with an average value of 8.2 liters per day, equal to 1.37 percent of the total water content of the system. Dissolved oxygen was significantly different among treatments, with the lowest median value recorded with the highest stocking density of fish (5.6 mg per liter) and the highest median value in the hydroponic control (8.7 mg per liter).

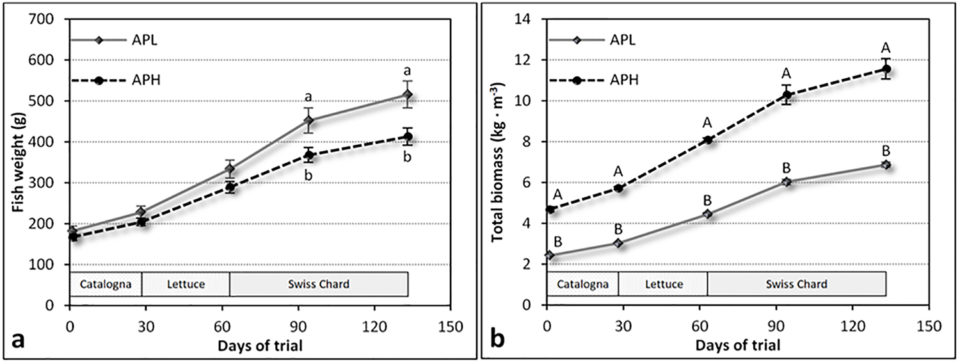

The marketable yield of the vegetables was significantly different among treatments, with the highest production in the hydroponic control for catalogna (1.2 kg per square meter) and in the APL treatment for Swiss Chard (5.3 kg per square meter). The yield of lettuce did not differ significantly between the hydroponic control and the APL system (4.0 kg per square meter on average). The lowest production of vegetables was obtained in the APH system. The final weight (515 grams vs. 413 grams for APL and APH, respectively), specific growth rate (0.79 percent d-1 vs. 0.68 percent d-1), and feed conversion (1.55 vs. 1.86) of European carp decreased when stocking density increased, whereas total yield of biomass was higher in the APH system (4.45 kg per cubic meter vs. 6.88 kg per cubic meter). A low mortality (3 percent on average) was observed in both AP treatments.

The concentration of dissolved oxygen observed in the water was lower in the APH systems than in the APL systems due to: i) a higher ratio between the weight of fish and the volume of the tank; and ii) a higher organic matter accumulation in the tanks with vegetables due to fish feed residues and feces, which may have increased the microbial consumption of oxygen.

Dissolved oxygen values were always above the reported lethal threshold for European carp (0.5 mg per liter), but to obtain an efficient nitrification, it should be above 2 mg per liter. This last condition was always observed in the outflow from the tanks of vegetables in APL units, showing that in this treatment, the biofilter had optimal conditions for nitrification. Conversely, in the APH system, the content of dissolved oxygen was sometimes lower than 2 mg per liter, indicating that the conditions for nitrification were not always optimal, as demonstrated by the NO3– concentration (near zero) in the APH water.

Regarding the vegetables cultured, our results showed that the yield in the hydroponic (HP) treatment was higher than in either of the aquaponics (AP) treatments only at the end of the first crop cycle. Thereafter, the yield in the HP was comparable to (lettuce) or lower (Swiss chard) than that observed in the APL treatment. The higher HP yield in the first cycle of crop was probably related to the incomplete maturation of the biofilter in the AP systems. This aspect, also reported by others, reduced the effective nitrification of the ammonium produced by fish, thus slowing the nitrogen availability for the plants.

During the experiment, after the full activation of the biofilter, the crop yields, especially in the APL, was comparable or higher than the control due to the continuous supply of N compounds from the fish and probably also due to the accumulation of several humic-like and protein-like dissolved organic matter components in the water that exert a stimulant effect. Considering the yield values, the production of catalogna was lower than results in open-field conditions; the production of lettuce, on the other hand, especially for HP and APL, was in line with data reported in other soilless experiments.

For the carps, their overall health was very good during the entire trial and only two fish died (one each in the APL and the APH treatments). These two animals died without previous symptoms of disease. At the end of the trial, fish weighed 446 grams on average, reaching a specific growth rate (SGR) of 0.74 percent per day. The feed conversion ratio for the whole period was 1.71, and the total biomass produced averaged 5.66 kg per cubic meter.

Growth performance of the fish differed significantly according to the stocking density used in the AP systems. Specifically, fish of the APL treatment showed higher SGR compared to the APH during most of the trial phases. Also, considering the entire rearing period, fish in the APL treatment had the highest SGR (0.79 percent per day vs. 0.68 percent per day for APL and APH, respectively). The higher the stocking density the higher the biomass of fish produced in the entire rearing period.No significant difference was found in terms of feed efficiency between the APL and APH systems. However, in general throughout the trial, feed conversions tended to be better in the APL treatment.

Perspectives

The stocking density of European carp influenced the yield of the tested AP system – better results, in terms of water quality and production of vegetables, were achieved with an initial stocking density of 2.5 kg per cubic meter. Moreover, growth and feed conversion of fish were negatively influenced by stocking density, but total biomass yield increased with increasing density of fish.

Considering the species-specific response of fish to different stocking densities, our findings are reliable for European carp, and further investigations are needed to establish the more suitable stocking densities for other species raised in AP. Good production of vegetables, performance and optimum health of fish suggest that the proposed low-tech system could be successfully implemented in the field on a larger scale and at low construction costs.

Now that you've finished reading the article ...

… we hope you’ll consider supporting our mission to document the evolution of the global aquaculture industry and share our vast network of contributors’ expansive knowledge every week.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year. GSA individual and corporate members receive complimentary access to a series of GOAL virtual events beginning in April. Join now.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Authors

-

Carmelo Maucieri, Ph.D.

Department of Agronomy Food Natural Resources Animal and Environment (DAFNAE)

University of Padova, Legnaro, Padova, Italy -

Carlo Nicoletto, Ph.D.

Corresponding author

Department of Agronomy Food Natural Resources Animal and Environment (DAFNAE)

University of Padova, Legnaro, Padova, Italy -

Giampaolo Zanin, Ph.D.

Department of Agronomy Food Natural Resources Animal and Environment (DAFNAE)

University of Padova, Legnaro, Padova, Italy -

Marco Birolo, Ph.D.

Department of Agronomy Food Natural Resources Animal and Environment (DAFNAE)

University of Padova, Legnaro, Padova, Italy -

Angela Trocino, Ph.D.

Department of Comparative Biomedicine and Food Science (BCA)

University of Padova, Legnaro, Padova, Italy -

Paolo Sambo, Ph.D.

Department of Agronomy Food Natural Resources Animal and Environment (DAFNAE)

University of Padova, Legnaro, Padova, Italy -

Maurizio Borin, Ph.D.

Department of Agronomy Food Natural Resources Animal and Environment (DAFNAE)

University of Padova, Legnaro, Padova, Italy -

Gerolamo Xiccato, Ph.D.

Department of Agronomy Food Natural Resources Animal and Environment (DAFNAE)

University of Padova, Legnaro, Padova, Italy

Tagged With

Related Posts

Innovation & Investment

Aquaculture Exchange: David Little, University of Stirling

David Little, professor at the University of Stirling in Scotland, tells the Advocate about the rapid evolution of the aquaculture industry in Southeast Asia — where he made his home for many years — and discusses the role of academia in ushering in new eras of innovation.

Health & Welfare

Integrated aquaponics systems evaluated for arid zones of Chile

Integrated aquaponic operations can improve water use efficiency because plants participate in nitrogen and phosphorus removal and integration.

Innovation & Investment

Connecticut ‘urban fish farm’ leans on RAS to produce branzino

The Ideal Fish “urban fish farm” in Connecticut is producing branzino, or European sea bass, using RAS technology. Learn about this project from the company that designed and supported it: Pentair Aquatic Eco-Systems.

Intelligence

Young aquaponics, aquaculture company gets big boost

Fluid Farms, an aquaponics produce grower in Maine, leans on multi-trophic aquaculture to provide nutrients for its plants. The company is now selling its hybrid striped bass to the local market and, armed with a $50,000 innovation prize that will fund a new heating system, is expanding its horizons.