Mixture of fresh feeds, dry broodstock pellet results in lower broodstock mortality for male and female P. vannamei

Interest in captive reproduction of penaeid shrimp is increasing worldwide due to the urgent need to establish selective breeding programs and produce certified, diseasefree postlarvae. An optimal diet is a crucial factor in the successful sexual maturation and reproduction of shrimp in breeding operations. High-quality food represents the highest operational cost in most broodstock management facilities. Maturation facilities in marine shrimp hatcheries depend mostly on fresh feeds, which can be inconvenient for operators. Dry artificial feeds, on the other hand, have several advantages, including reliable supply, consistent and controlled quality, and ease of handling. Artificial diets also reduce fouling of larval tanks, cut risk for disease transfer, and offer effective delivery of chemotherapeutics, immunostimulants and hormones. Trials in Ecuador and New Caledonia indicated that the incorporation of artificial feeds in broodstock diets can improve broodstock performance in several areas.

A dry, off-the-shelf broodstock feed was formulated to provide optimal palatability, stability, and nutrition for broodstock shrimp (Table 1). The diet contains no marine protein sources derived from aquaculture, and provides a constant supply of all known essential nutrients for broodstock maturation. These include highly unsaturated fatty acids of the omega-3 and -6 families, phospholipids, cholesterol, carotenoids, vitamins, minerals, artemia and squid factors. The combination of appropriate extrusion and binder technology resulted in high water stability.

Coutteau, Nutritional profile of INVE Breed-Shrimp, Table 1

| Component | Unit | Specifications |

|---|

Component | Unit | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Moisture | % | < 10 |

| Crude fiber | % | < 4 |

| Crude protein | % | > 50 |

| Crude fat (hydrolysis) | % | > 10 |

| Essential Fatty Acids | ||

| ARA (20:4n-6) | mg/g DW | > 1.5 |

| EPA (20:5n-3) | mg/g DW | > 5 |

| DHA (22:6n-3) | mg/g DW | > 10 |

| n-3 HUFA (≥ 20:3n-3) | mg/g DW | > 20 |

| n-6 PUFA (≥ 18:2n-6) | mg/g DW | > 10 |

| Vitamin C | mg/kg | > 3,000 |

| Vitamin A | IU/kg | > 20,000 |

| Vitamin D3 | IU/kg | > 8,000 |

| Vitamin E | mg/kg | > 800 |

Maturation test with P. vannamei

The feed was evaluated under commercial conditions as a partial substitute for fresh feeds during a 39-day maturation trial with P. vannamei at the Quirola Group’s Quimasaru hatchery in Ecuador. The experiment used 16 maturation tanks (eight per treatment), each stocked with approximately 80 wild-caught shrimp at a sex ratio 1:1. Shrimp of 40 grams average body weight were acclimated and ablated prior to stocking. Natural photoperiod was used, with a 50 percent daily water exchange and temperature of 29 to 30 degrees-C.

During Period I, the first 19 days of the experiment, shrimp in the control tanks were fed solely on a mixture of fresh feeds that included enriched artemia biomass, mussels, squid, bloodworms, and shrimp heads. Contrary to current practice, the shrimp heads and other potentially risky feed elements were included because there was no white spot syndrome virus alert at the time of the trial.

The other group was fed a reduced ration of fresh feeds in combination with the dry pellets. Overall, fresh feed replacement approximated 50 percent on a dry-matter basis, but was different for each type of fresh feed fed to the control tanks.

During the experiment, the hatchery operator wanted to benefit from the reduced mortality due to the supplementation of the broodstock feed. Therefore, the two groups were switched to the same feeding regime in the final period. Both groups received a mixture of about 80 percent fresh feeds and 20 percent dry pellets during Period II, the last two weeks of the experiment.

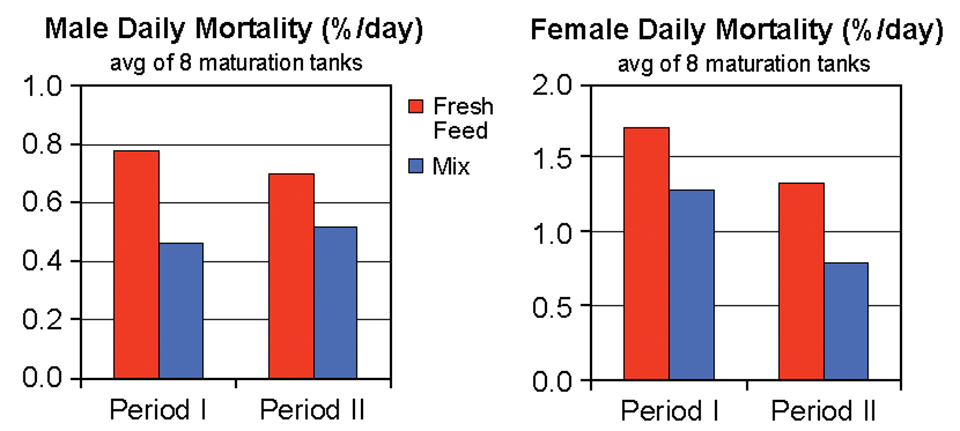

Mortality

High mortality after ablation of wild broodstock, with higher mortality observed in females, was an important problem during production runs. During Period I, animals fed the mixed diet had lower mortalities than animals fed just the fresh diet (Fig. 1). During Period II, overall mortality rate was reduced, and the effect of the dry feed supplement during the previous period remained important.

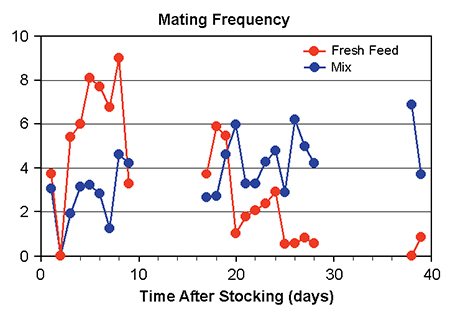

Mating

Mating frequency (daily percentage of females fertilized, through artificial insemination or natural mating) was considerably higher during Period I for broodstock fed the fresh feed (Fig. 2). The proportion of natural insemination was 40 to 55 percent. However, during Period II the percentage of successfully fertilized females dropped in the shrimp fed fresh feeds. Overall, a more consistent mating throughout the production run was obtained in the group that received the supplemented broodstock feed.

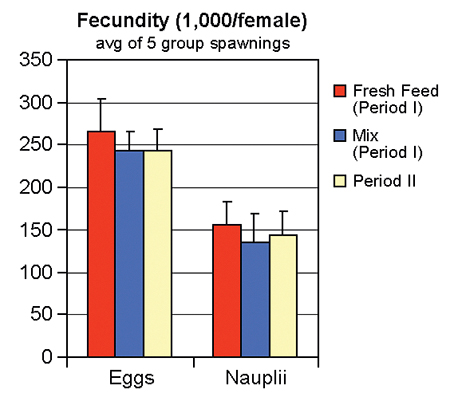

During Period I, average fecundity of 245,000 eggs and 135,000 nauplii/female for the broodstock fed the mixed diet compared to 260,000 eggs and 152,000 nauplii/female for animals fed solely fresh feed (Fig. 3). This reflected 9 percent lower egg production and 14 percent fewer nauplii (no significant differences) in the group fed the mixed diet.

Fertilization percentages, which averaged 58 to 60 percent, were similar in both treatments. During Period II, average fecundity remained at an intermediate level compared to Period I (243,000 eggs and 144,000 nauplii/female).

Maturation test with p. stylirostris

Three trials were run with P. stylirostris at La Station d’Aquaculture de Saint-Vincent, an IFREMER facility in New Caledonia. Females were held at three animals per square meter in round, 4-meter-diameter tanks under typical maturation conditions of 29 to 30 degrees-C, with 50 percent water exchange/day and reversed photoperiod. Eyestalk ablation was performed.

The control feeding regime consisted of a mixture of fresh feeds (squid, mussels, and shrimp) and a small ration of dry commercial pellets. In the experimental regime, 50 percent of the fresh feed was replaced by the dry broodstock feed INVE Breed-Shrimp (Table 2).

Coutteau, Dietary regimes tested for maturation, Table 2

| Treatment | Squid | Mussels | Shrimp | Dry Pellet | Broodstock Feed |

|---|

Treatment | Squid | Mussels | Shrimp | Dry Pellet | Broodstock Feed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh feed | 7.3% | 6.1% | 2.5% | 0.5% | 0% |

| 50/50 diet | 3.7% | 3.1% | 1.2% | 0.5% | 2% |

No major difference in overall performance between the two dietary regimes was noticed over 18 days during the trials (Table 3). However, some interesting effects were observed in successive spawns. Fertilization rate and number of nauplii per spawn, which did not show global differences between treatments in any of the trials, decreased in trial 1 with successive spawns in the fresh feed regime, whereas these parameters improved with successive spawns in the mixed dietary regime (Fig. 4).

Coutteau, Average female performance and nauplii quality, Table 3

| Parameter | Fresh Feed | 50/50 Mix |

|---|

Parameter | Fresh Feed | 50/50 Mix |

|---|---|---|

| Female Performance | ||

| Female survival % | 60 ± 33 | 59 ± 18 |

| Maturations/month/female | 3.2 ± 1.1 | 3.4 ± 1.4 |

| Eggs/female/spawn (x 1,000) | 251 ± 57 | 241 ± 50 |

| Fertilization % | 55 ± 11 | 53 ± 14 |

| Hatching % | 74 ± 16 | 73 ± 19 |

| Nauplii/female/spawn (x 1,000) | 112 ± 19 | 99 ± 20 |

| Nauplii Quality | ||

| Deformity index (0-5) | 4.7 ± 0.2 | 4.8 ± 0.1 |

| Activity index (0-5) | 4.7 ± 0.1 | 4.8 ± 0.1 |

| Survival to zoea I in culture (%) | 65 ± 8 | 75 ± 11 |

Also, although no significant differences could be detected in overall survival rate from nauplii to zoea I, survival decreased drastically in the last week of the maturation trial in the fresh feed treatment. This was not the case for the 50/50 mixed regime (Fig 5). These results showed that the nutritional boost provided by the broodstock pellet supported more sustainable reproductive activity and goodquality offspring through repetitive spawnings.

Conclusion

A maturation diet consisting of a mixture of fresh feeds supplemented with a dry broodstock pellet produced lower broodstock mortality for male and female P. vannamei following ablation and more consistent mating throughout the production cycle than a diet of fresh feeds. Comparable fecundity and fertilization rates were recorded for both feed types in trials.

The replacement of 50 percent of fresh feed with dry feed for P. stylirostris broodstock resulted in similar female reproductive response rates and similar larval quality (deformities, activity, and survival) when compared to animals fed the control diet. The mixed diet also improved fecundity and larval quality over repeated spawnings.

(Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the June 2001 print edition of the Global Aquaculture Advocate.)

Now that you've finished reading the article ...

… we hope you’ll consider supporting our mission to document the evolution of the global aquaculture industry and share our vast network of contributors’ expansive knowledge every week.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year. GSA individual and corporate members receive complimentary access to a series of GOAL virtual events beginning in April. Join now.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Authors

-

P. Coutteau

INVE Technologies N.V.

Oeverstraat, Belgium -

E. Dencece

IFREMER – Station d’Aquaculture de Saint-Vincent

Boulouparis, New Caledonia -

D. Pham

IFREMER – Station d’Aquaculture de Saint-Vincent

Boulouparis, New Caledonia -

E. Pinon

Guayaquil, Ecuador

-

Y. Balcazar

Grupo Quirola

Division Laboratories – Guayaquil, Ecuador

Related Posts

Health & Welfare

Advances in fish hatchery management

Advances in fish hatchery management – particularly in the areas of brood management and induced spawning – have helped establish aquaculture for multiple species.

Health & Welfare

10 paths to low productivity and profitability with tilapia in sub-Saharan Africa

Tilapia culture in sub-Saharan Africa suffers from low productivity and profitability. A comprehensive management approach is needed to address the root causes.

Aquafeeds

Fishmeal, fish oil replacements in sea bream, sea bass diets need nutritional compensation

Fishmeal and fish oil replacements present a challenge for the aquafeed industry. The range of alternative protein and fat sources is limited, given multiple considerations.

Health & Welfare

Alfalfa concentrate: natural shrimp color enhancer

Adding alfalfa concentrate containing natural carotenoids and pigments to the finishing diets of shrimp can enhance coloration of shrimp after cooking.