Gracilaria chilensis remains the only commercially cultivated species

Over the last 15 years, seaweed utilization in Chile reached a volume of over 300,000 metric tons (MT, wet weight) per year. Half this production included various species of brown algae (Phaeophyta) and the other 50 percent were harvested red algae (Rhodophyta). Algal production in Chile is mainly based upon wild stocks, with commercial-scale cultivation so far limited to Gracilaria chilensis. Advances toward a more diversified seaweed aquaculture industry are currently being made, however.

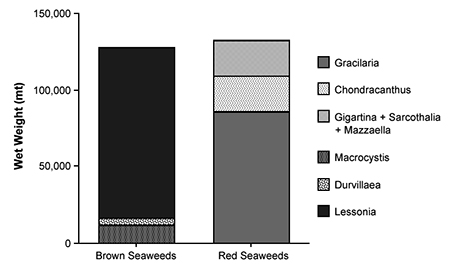

Total landings of brown algae reached 128,261 MT in 1999, with Lessonia nigrescens dominating production (Fig. 1). L. nigrescens and L. trabeculata are collected and processed for their alginate. Experimental cultivation of L. trabeculata has been carried out in northern Chile.

As a result of the expanding abalone culture industry in Chile, there is significant interest in open-sea culture of Macrocystis pyrifera as abalone feed. Pilot production of this kelp is now under way in southern Chile.

The bull kelp (Durvillaea antarctica) is used for human consumption in local markets. M. pyrifera culture has also been evaluated to obtain products for human consumption. However, further development of commercial-scale culture techniques is necessary.

Several red algae species are currently taken in Chile, with total landings of 133,219 MT in 1999. Commercial culture of Gracilaria chilensis can be profitable, which has stimulated the activity in recent years. Prices have been highly variable over the past 10 years, however, so it seems important to optimize production by lowering costs and increasing productivity.

Production techniques

Several planting techniques have been developed to fasten Gracilaria to the substratum (Buschmann et al. 1995). Regardless of the planting method, production relies upon the capacity of Gracilaria to develop an underground thallus system that anchors the algae to the soft bottom.

After planting, beds are maintained by vegetative growth from the underground thallus system, which is able to survive burial for several months. As the topography of the sandy substratum changes with water currents, buried thalli become exposed to light and growth begins.

For subtidal areas in southern Chile, Gracilaria production can reach 150 MT per hectare per year. In contrast, intertidal systems established at the same latitude are less productive, with biomass levels never exceeding 72 MT per hectare per year. Production in northern Chile is generally higher than in the south, apparently related to the higher temperatures and longer light regimes in the north.

Problems

Several problems affect Gracilaria production. After two or three years of high yields, farmers often experience an abrupt drop in productivity. Over-exploitation of several wild Gracilaria stands could limit further development of farming activities, because some of the larger genetic reserves for the species have been destroyed. The persistent use of the same culture area triggers the development of pests that affect the Gracilaria.

Pest control

Several methods have been suggested to control pest organisms in seaweed cultures. Most of these methods are only suitable for tank culture, and are difficult to apply successfully in open culture areas. Improved understanding of recruitment patterns, mechanisms of host infection, and biological control techniques will be required when selecting management strategies for reducing pest organisms in Gracilaria farms.

Alternative production technology

Research efforts are under way to develop alternative production technologies for Gracilaria. Intertidal enclosures can be installed high in the intertidal zone, where the tidal regime exchanges seawater twice daily. This approach yields 30 percent greater biomass production than the traditional intertidal farms. Tank cultivation of G. chilensis has also been undertaken, but this type of culture has not attracted private investors because it is not profitable.

To improve profitability, tank cultivation integrated with a salmon farm was developed. This system is highly productive, and does not involve additional pumping, nutrient and carbon dioxide costs. The Gracilaria reduce the negative impact of fish waste, while most of the costs for cultivating the algae are covered by the operational costs of the salmon farm. A further advantage is that algae cultivated with fish wastewater have a higher agar quality.

Carrageenan demand

The demand for carrageenophytic seaweeds along the Chilean coast has increased in recent years, mainly related to the establishment of processing plants to extract the colloid. The supply of these species relies on the harvesting of wild stocks of Sarcothalia crispata, Mazzaella laminarioides and Gigartina skottsbergii. Several research groups are currently working to develop mariculture strategies and techniques for these species.

There are no reports to date of hatchery-produced Gigartina germlings cultivated in open systems. This points to two bottlenecks for future development of Gigartina mariculture: the seasonal availability of spores, and their low germination and growth potential. For this reason, efforts have been made to propagate this species vegetatively. Laboratory experiments have shown that Gigartina has a high healing and regeneration capacity.

These results encouraged further experiments in nursery facilities, which have shown that fragmentation of the fronds is technically feasible, and that healing and regeneration responses can be optimized by experimental manipulation of temperature, light and nutrient concentrations. Explants of Gigartina fronds have also been cultivated in floating ropes in southern Chile, demonstrating they can regenerate surface at increments of 90 to 250 percent over a six-month period during the summer.

Other species

At least one study has demonstrated that cultivation of the Chilean nori (Porphyra columbina) is biologically feasible. Nevertheless, the limited local market is not sufficiently attractive to stimulate the investment required to cultivate this species on a commercial scale.

During the last three years, markets have opened in Chile for Callophyllis variegata and Chondracanthus chamissoi. Knowledge related to these species is largely restricted to distribution data, although some information regarding phenology and spore handling in the laboratory is now available for C. chamissoi.

For C. variegata, carpospores are available during the winter, whereas tetraspores are available during spring. Furthermore, natural populations of C. variegata are also being studied to develop management recommendations. It has been demonstrated that the holdfast of this species has a high regeneration capacity, which enables the harvested population to recover.

The seaweed production industry in Chile has diversified significantly over the last 10 years, reflected in the development of the carrageenan industry, increased production of agar, and the addition of such highly valuable species as the edible seaweed Callophyllis variegata to Chilean exports. Also, the number of species being processed and marketed has increased.

Gracilaria chilensis remains the only commercially cultivated species, but this is expected to change in the near future. Tank culture of algal species has not been developed on a commercial scale, although efforts are being made to develop integrated, land-based fish, mollusk and seaweed farming systems. Experimental cultivation of brown algae has developed very fast during the last two years, and commercial cultivation of Macrocystis pyrifera for abalone feed and direct use by humans is expected to be a reality soon.

Note: Cited references are available from the first author.

(Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the June 2001 print edition of the Global Aquaculture Advocate.)

Now that you've finished reading the article ...

… we hope you’ll consider supporting our mission to document the evolution of the global aquaculture industry and share our vast network of contributors’ expansive knowledge every week.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year. GSA individual and corporate members receive complimentary access to a series of GOAL virtual events beginning in April. Join now.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Authors

-

-

María Carmen Hernández-González

Universidad de Los Lagos

Osorno, Chile -

Gesica Aroca

Universidad de Los Lagos

Osorno, Chile -

Alfonso Gutierrez

Universidad de Los Lagos

Osorno, Chile

Tagged With

Related Posts

Innovation & Investment

Aquaculture Exchange: Sebastian Belle

The executive director of the Maine Aquaculture Association talks to the Advocate about the diverse and growing industry in his state (oysters, mussels, kelp, eels and salmon) and how aquaculture should be used as a rural development tool.

Responsibility

Can sustainable mariculture match agriculture’s output?

Global, sustainable mariculture production, developed on a massive, sustainable scale and using just a small fraction of the world’s oceanic areas, could eventually match the output of land-based agriculture production. Scale and international law considerations require the involvement of many stakeholders, including national governments and international organizations.

Responsibility

Lease, seed and repeat: GreenWave’s replicable aquaculture

Don’t call it integrated multi-trophic aquaculture: Former commercial fisherman Bren Smith says polyculture of non-fed species is the future of aquaculture.

Responsibility

Lean and green, what’s not to love about seaweed?

Grown for hundreds of years, seaweed (sugar kelp, specifically) is the fruit of a nascent U.S. aquaculture industry supplying chefs, home cooks and inspiring fresh and frozen food products.