Virus examined at University of Arizona Aquaculture Pathology Laboratory

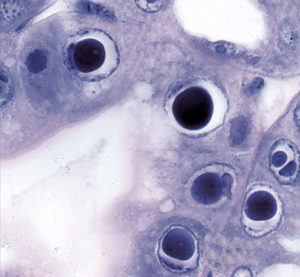

Hepatopancreatic parvovirus (HPV) is a small icosahedral, nonenveloped virus containing a single-stranded linear DNA genome that is placed as a member of (Parvorividae). There is no specific gross sign for HPV-infected shrimp, but histology reveals the presence of intranuclear inclusion bodies in hepatopancreatic tubule epithelial cells

Discovered in cultured (Penaeus merguiensis) in Singapore in 1982, the virus has been associated with poor growth and mortalities up to 100 percent in larval and postlarval penaeids. It has since been detected in (P. chinensis), (P. semisulcatus), (P. monodon), (P. stylirostris) and (P. vannamei). HPV has been found in both cultured and wild stocks in Southeast Asia, the Middle East, the Americas, Oceania and Africa.

HPV variation

The authors’ laboratory at the University of Arizona maintains an archive of samples of shrimp infected with HPV received from around the world. This has afforded the opportunity to study genetic variation among isolates collected over a wide geographic area.

In recent work, the nucleotide sequences of HPV isolates from Madagascar and Tanzania were compared with HPV sequences deposited in the GenBank genetic sequence database from Korea, Thailand and Australia. Samples of HPV-infected juvenile P. monodon were collected from a farm in Madagascar in 2007. HPV-infected postlarval P. monodon from Tanzania were sent from a farm near Dar es Salaam in 2008.

DNA was extracted from the hepantopancreas tissue and amplified with HPV-specific primers. The purified and sequenced amplicons indicated 5,742 and 5,685 base pairs of Madagascar and Tanzania HPV, respectively.

Sequence analysis

The overall mean distance or percentage of difference in nucleotides among the five isolates was 17 percent, with the largest (21 percent) distance between Thailand and Australia isolates. At 12 percent, Madagascar HPV was closest to the Tanzania isolate.

The amino acid sequences of the open reading frames were also compared among the five isolates. ORF is a DNA sequence that could potentially encode a protein. For the left ORF, the overall mean distance was 13 percent. The mid ORF had the lowest (7 percent) distance. The right ORF, which encodes the viral capsid protein, had the highest (24 percent) distance.

In general, the coding sequences for viral structural protein had higher variation than those coding for nonstructural proteins, which are responsible for viral DNA or RNA replication and usually more conserved.

The study revealed a high level of genetic variation among the isolates. HPV appears to have greater genetic diversity than other shrimp viruses such as infectious hypodermal and hematopoietic necrosis virus (IHHNV) and Taura syndrome virus (TSV), which may reflect the fact that it is found over a much wider geographic area than the others.

Phylogenetic analysis

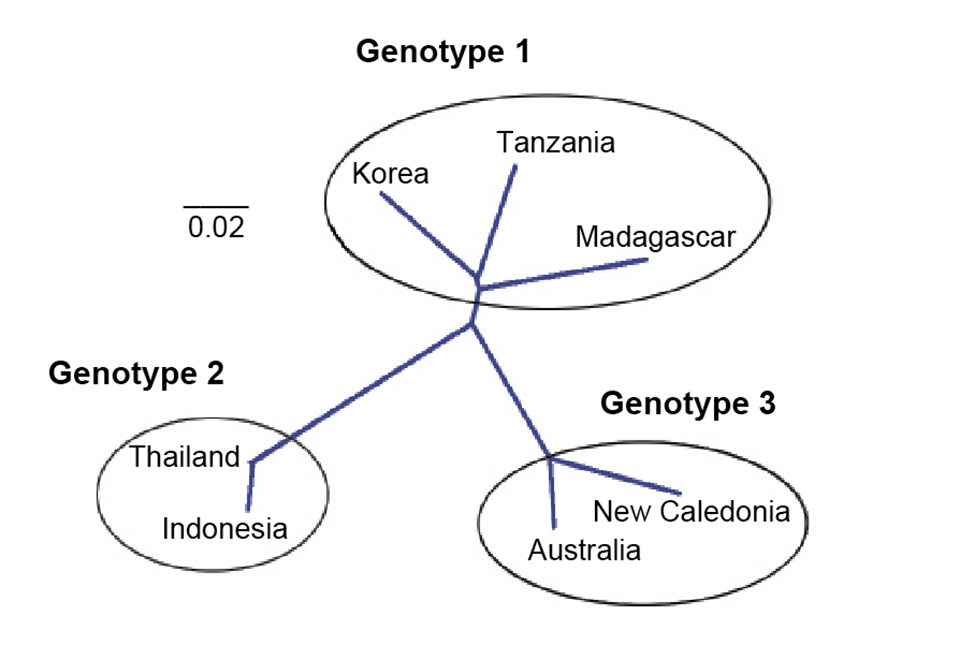

The amino acid sequences of the right ORF were used to construct a phylogenetic tree. Seven isolates representing three genotypes were included in the analysis: type 1 (Korean, Madagascar, Tanzania), type 2 (Thailand and Indonesia) and type 3 (Australia, and New Caledonia).

The two Africa isolates and that from Korea were grouped with a bootstrap value of 75 percent, which is not strong and should be considered tentative until more isolates are analyzed. The isolates from New Caledonia and Australia clustered into one group. HPV from Indonesia and Thailand are closely related and were clustered together. The isolate clusters reflect geographic distribution of the samples.

Impacts of HPV infection

Although HPV may be highly infectious in wild populations, its effects on shrimp growth are not clear. A 95 percent prevalence of HPV was found in wild populations of P. merguinesis in New Caledonia, and P. monodon in Madagascar had 90 percent prevalence. This suggested that HPV is very transmissible in the wild, but reports on the impacts of this virus on farmed shrimp are conflicting.

HPV has been linked to growth reduction in farmed P. monodon in Thailand, but in Madagascar, HPV infection appears to have no negative effect on shrimp growth. The various effects reported from different areas may be related to differences among viral genotypes, host populations and/or farming practices. For example, the Thailand isolate differs from Madagascar isolate by 20 percent in nucleotide sequence and was shown to be a different genotype. Populations of P. monodon in the Indian Ocean are genetically different from those of the western Pacific Ocean.

Also, high stocking density is known to result in reduced growth due to competition for space and food. In Madagascar, the shrimp were cultured at a stocking density of 10-15 per square meter, while those in Thailand are generally stocked at over 75 per square meter. Therefore, the stunted growth reported in HPV-infected P. monodon cultured in Thailand may be related to the high stocking density.

Madagascar HPV

African stocks of P. monodon are often used as broodstock in other areas of the world because they are free of the major infectious shrimp viruses: white spot syndrome virus, TSV, IHHNV, yellow head virus and infectious myonecrosis virus. However, in Madagascar and Mozambique, nearly 100 percent of both the wild and farmed populations are infected with HPV.

The effects of Madagascar HPV on shrimp growth need to be clarified through controlled experiments. If Madagascar HPV negatively impacts shrimp growth, then stocks need to be monitored for HPV prior to shrimp being stocked in grow-out ponds or exported as broodstock.

(Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the July/August 2008 print edition of the Global Aquaculture Advocate.)

Now that you've finished reading the article ...

… we hope you’ll consider supporting our mission to document the evolution of the global aquaculture industry and share our vast network of contributors’ expansive knowledge every week.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year. GSA individual and corporate members receive complimentary access to a series of GOAL virtual events beginning in April. Join now.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Authors

-

Kathy F.J. Tang, Ph.D.

Department of Veterinary Science and Microbiology

University of Arizona

Tucson, Arizona 85721 USA[117,100,101,46,97,110,111,122,105,114,97,46,117,64,117,121,106,103,110,101,102]

-

Carlos R. Pantoja, Ph.D.

Department of Veterinary Science and Microbiology

University of Arizona

Tucson, Arizona 85721 USA -

Donald V. Lightner, Ph.D.

Department of Veterinary Science and Microbiology

University of Arizona

Tucson, Arizona 85721 USA

Related Posts

Health & Welfare

A study of Zoea-2 Syndrome in hatcheries in India, part 1

Indian shrimp hatcheries have experienced larval mortality in the zoea-2 stage, with molt deterioration and resulting in heavy mortality. Authors investigated the problem holistically.

Health & Welfare

Designing a biosecurity plan for shrimp aquaculture, part 2

The objective of a contingency plan is to quickly recover production through rapid initial response and effective implementation of biosecurity measures. Such plans depend on whether the detected pathogen or disease is exotic or endemic, its potential economic impacts and whether it is to be eradicated.

Health & Welfare

Brunei project develops technology for large black tiger shrimp production, part 2

For a five-year project undertaken in Brunei Darussalam to develop advanced technology for production of large black tiger shrimp, a comprehensive disease diagnostic laboratory was developed to enable detection of known and emerging shrimp pathogens by molecular and histological methods.

Health & Welfare

The history and future of the Aquaculture Pathology Laboratory

The University of Arizona’s Aquaculture Pathology Laboratory has significantly contributed to the expansion of the shrimp farming for three decades.