Does trace contamination at levels as low as 0.1 μg per kilogram really constitute a hazard to human health?

Chloramphenicol is an antibiotic that was originally isolated from Streptomyces venezuelae and now is produced synthetically. It is not approved for use in food animals by the European Union (E.U.) or the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Last August, German health authorities found residues of chloramphenicol in a shipment of shrimp from China. Subsequent surveillance within the E.U. also detected trace levels of chloramphenicol in shrimp from Vietnam and Indonesia. As a result, all consignments of shrimp from those countries to the E.U. must now be sampled before entry “to demonstrate their wholesomeness.” Also, FDA recently issued Import Alert 16-124, which calls for detention of aquaculture products due to unapproved drugs.

Potential human health risk

In general, antibiotic use presents three areas of concern: residues in foods destined for human consumption, development of drug resistance in human pathogenic bacteria, and direct toxic effects to humans from handling drugs. Chloramphenicol is considered a drug of last resort for use in human medicine, because excessive exposure can cause potentially fatal aplastic anemia in one of 30,000 individuals treated.

In general, antibiotic use presents three areas of concern: residues in foods destined for human consumption, development of drug resistance in human pathogenic bacteria, and direct toxic effects to humans from handling drugs. Chloramphenicol is considered a drug of last resort for use in human medicine, because excessive exposure can cause potentially fatal aplastic anemia in one of 30,000 individuals treated.

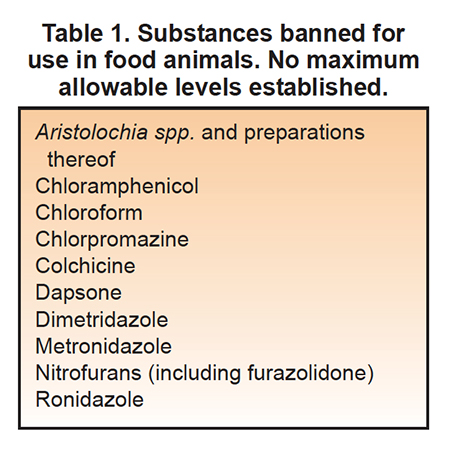

FDA banned its use for treatment of bacterial diseases of ornamental fish due to hazards associated with handling of the antibiotic. Since 1990, European Commission regulations on veterinary medical products prohibit chloramphenicol and nine other “pharmacologically active substances” from being administered to food animals (Table 1).

Origin of chloramphenicol

The origin of chloramphenicol residues in Asian shrimp is not clear. Possibilities include:

- Addition of chloramphenicol to water used to rear shrimp larvae in hatcheries.

- Inclusion in feeds used to rear shrimp in ponds.

- Inclusion in bactericide mixtures intended to disinfect processing equipment or reduce the superficial bacterial load of shrimp.

- Use as a medicine by people that come in contact with shrimp.

- Presence as a natural contaminant in mold within feedstuffs or the aquatic environment.

Unclear standards

Although European Commission guidelines call for its member states to apply “appropriate sampling plans and detection methods” in the search for chloramphenicol, they do not offer clearly established standards. In addition, the commission fails to clearly specify what action is to be taken if a sampled shipment fails the tests.

Earlier directives on imported products involving veterinary-related checks said if shipments do not satisfy stated conditions, the person responsible for a load has up to 60 days to reship the items to a destination where competent authorities do not object to importing the goods. However, if the consignment is considered to “constitute a danger” to animal or human health, the competent veterinary import inspection authority must seize and destroy the shipment.

Added costs

Analysis for chloramphenicol residues is costly in both time and fees. In Belgium, for example, seven test samples are needed for shipments up to 500 master cartons, and 15 are required for shipments that total 1,200-3,200 master cartons. The analytical cost by gas chromatography is about U.S. $120 per sample. Containers of seafood must remain in demurrage for two to four weeks while analyses are done.

Conclusion

At this time, traces of chloramphenicol have been found in shrimp from China, Vietnam, and Indonesia. But one could argue whether trace contamination at levels as low as 0.1 μg chloramphenicol per kilogram shrimp really constitutes a hazard to human health, and whether these traces might have originated from natural sources. Nevertheless, in the European Union, regulations can lead to rejection – and even seizing and destruction – of shipments that reflect even very low levels of chloramphenicol. Consequently, it is important that all stakeholders in the global seafood industry take the necessary measures to assure that absolutely no chloramphenicol or products containing it are used in the production or processing of shrimp.

(Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the December 2001 print edition of the Global Aquaculture Advocate.)

Now that you've finished reading the article ...

… we hope you’ll consider supporting our mission to document the evolution of the global aquaculture industry and share our vast network of contributors’ expansive knowledge every week.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year. GSA individual and corporate members receive complimentary access to a series of GOAL virtual events beginning in April. Join now.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Author

Tagged With

Related Posts

Health & Welfare

Chloramphenicol in shrimp: Europe as food safety utopia

The detection of the antibiotic chloramphenicol in shrimp exported to Europe from Asian countries brought about a flood of reactions.

Health & Welfare

Chloramphenicol revisited

Zero tolerance for chloramphenicol residue in food by the European Community indicates that chloramphenicol risks are regarded as real by European regulators.

Health & Welfare

Antibiotic-resistant bacteria, part 1

No antimicrobial agent has been developed specifically for aquaculture applications. However, some antibiotic products used to treat humans or land-based animals have been approved for use at aquaculture facilities.

Intelligence

What’s in your fish? FDA reinforces aquaculture drug policy

Drug-related import refusals at U.S. ports were up in 2015 for the third straight year. Representatives from the National Fisheries Institute and the Food and Drug Administration discussed U.S. aquaculture drug policy at Seafood Expo North America and how the supply chain can avoid problems.