Feeding trial evaluates natural and less expensive alternative

The demand for cooked shrimp in retail markets is increasing in most of the main importing countries in Europe. In France, over 50 percent of imported shrimp are sold as cooked and chilled head-on. The demand for cooked, chilled shrimp is also increasing in Spain, the United States, Australia, and even Japan.

Supply to these main markets is also increasing, requiring shrimp producers and exporters to improve the quality control of their products. The aesthetic characteristics of products are among the first criteria that influence shrimp buyers.

Market importance of coloration

The reddish color of cooked shrimp is one of the most attractive attributes and important quality criteria for most consumers. Unfortunately, farmed shrimp are sometimes slightly underpigmented, resulting in pale coloration.

Color is one of the major factors considered in price determinations. For example, Indian white shrimp (Penaeus indicus), from the Middle East are an excellent product, yet are often rejected by French and Spanish industrial cookers because they are too pale. The same problem occurs with some lightly pigmented Pacific white shrimp (P. vannamei).

Enhancing coloration

Wild-caught shrimp are generally well pigmented because their diets supply pigments through ingestion of microalgae and zooplankton. In farmed shrimp, pigment deficiencies can be due to the species, farming conditions, or deficiency in pigment precursors in the raw materials used in aquafeeds.

Various natural products rich in carotenoids, such as spirulina, paprika, or synthetic astaxanthin, have been tested in various commercial feeds to enhance shrimp color. However, the cost of including these products can be high.

One natural – and less expensive – alternative to effectively enhance shrimp pigmentation is to include in shrimp feed an alfalfa concentrate known as Pigmentech, which is produced by the dehydration of this forage crop. The process involves water extraction, heat, and physical handling. Recent trials evaluated the effects of this alfalfa concentrate on shrimp coloration when incorporated into shrimp feed.

Lucien-Brun, Composition of diets, Table 1

| Ingredient | Diet T | Diet A | Diet B |

|---|

Ingredient | Diet T | Diet A | Diet B |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fishmeal | 30.0% | 30.0% | 30.0% |

| H FPC | 3.0% | 3.0% | 3.0% |

| Soybean meal | 10.0% | 10.0% | 10.0% |

| Yeast | 5.0% | 5.0% | 5.0% |

| Wheat | 38.0% | 34.0% | 30.0% |

| Cod liver oil | 3.0% | 3.0% | 3.0% |

| Lecithin | 2.0% | 2.0% | 2.0% |

| Rovimix | 2.0% | 2.0% | 2.0% |

| NoHP04 | 1.0% | 1.0% | 1.0% |

| CaC03 | 0.5% | 0.5% | 0.5% |

| CaHPO4 | 0.5% | 0.5% | 0.5% |

| Wheat gluten | 5.0% | 5.0% | 5.0% |

| Alfalfa concentrate | 0% | 4.0% | 8.0% |

| Analysis | |||

| Moisture | 10.9% | 9.3% | 10.6% |

| Protein | 34.0% | 34.5% | 39.5% |

| Lipids | 8.8% | 9.7% | 9.9% |

| Ash | 8.4% | 8.5% | 8.8% |

Feeding trial

Dr. Gerard Cuzon and coworkers at IFREMER in French Polynesia carried out a trial with Pacific blue shrimp (Penaeus stylirostris) fed finishing diets during the last month of grow-out that included the alfalfa concentrate at inclusion rates of 4 and 8 percent with six replicates. A control diet contained no concentrate. The compositions of the experimental diets, which had somewhat different levels of protein and lipids, are shown in Table 1.

The experiment was conducted in clear-water tanks under controlled water quality conditions. The animals were individually weighed at the start of the trial and fed 3-4 times per day at about 5 percent biomass daily.

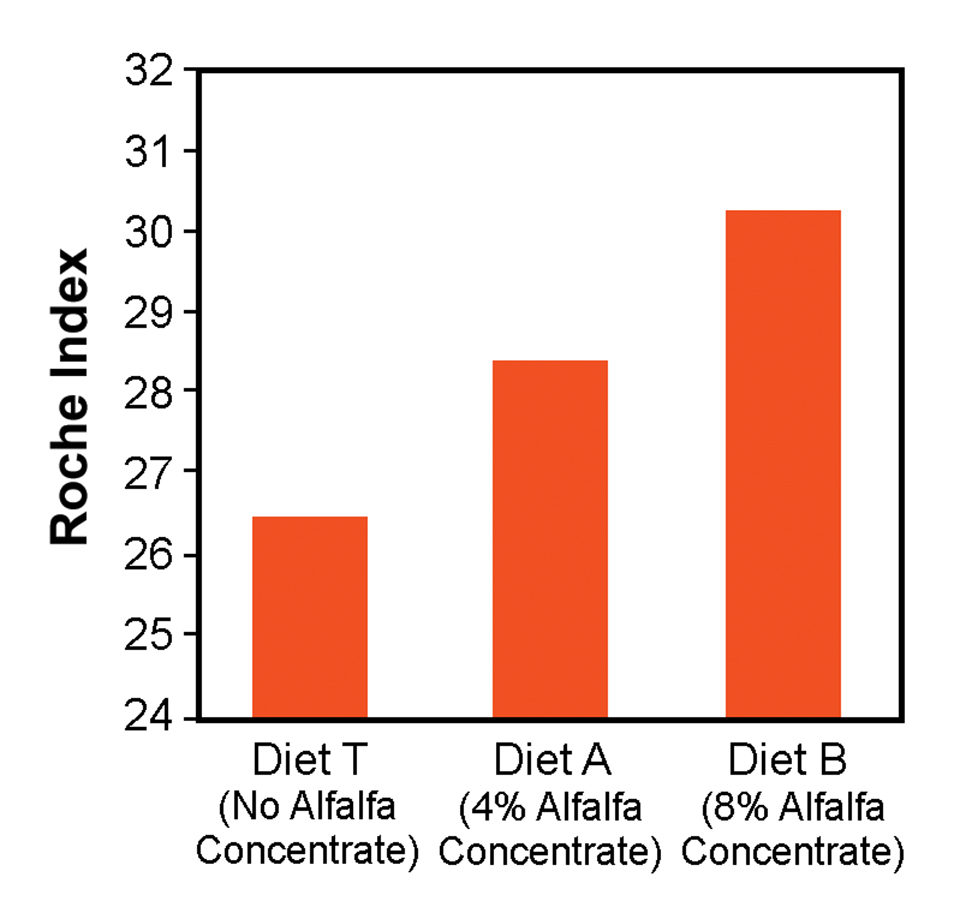

On days 7 and 21, six shrimp per treatment and sampling were immersed in boiling water for three minutes and placed on a black and/or white area to evaluate coloration using the Roche index, which assigns higher values for more intense coloration. Shrimp color was evaluated by a team of 10 people.

On day 7, there was no statistical difference between treatments. On day 21, however the shrimp fed the diets with alfalfa concentrate had significantly enhanced coloration after cooking. The average Roche indices were 26.4 for animals fed the control diet, 28.3 for the diet with 4 percent alfalfa concentrate, and 30.2 for the diet with 8 percent concentrate (Fig. 1).

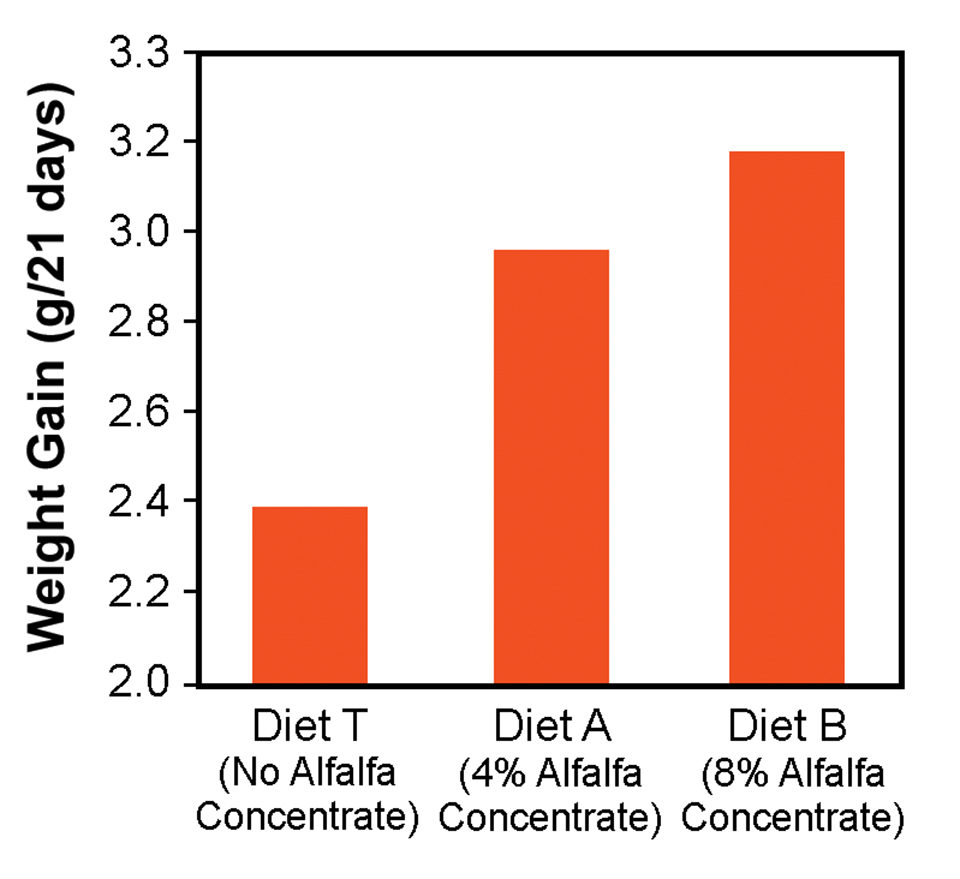

The alfalfa concentrate also improved animal performance, particularly weigh gain (Fig. 2), possibly due to the high digestibility of alfalfa protein and its high content of natural antioxidants and essential fatty acids. No differences were observed between diets in terms of molting rate or survival.

Carotenoid content

A second trial in Tahiti by O. Berticat of the University of Montpelier, France, and R. Castillo and G. Nègre-Sadargues of IFREMER described the nature of the pigments involved in shrimp coloration after bioconversion.

Three six-animal batches (T, A, and B) of shrimp from the first trial were deep frozen at -80 degrees C, while another sample batch (P) was collected from earthen culture ponds at a semi-intensive farm in- Tahiti. Qualitative analyses of the levels of carotenoids in the shell, epidermis, and hepatopancreas of the individual shrimp were carried out by chromatography.

Tables 2 and 3 show the results of these analyses, with an evident increase of carotenoid concentrations in the epidermis and hepatopancreas of shrimp from batch T to batch B. The results explained the better coloration and demonstrated the biometabolism of the alfalfa extract carotenoids into natural astaxanthin. With very low concentrations of carotenoids, the shrimp shells were essentially translucent, while the epidermis had higher levels of pigments. These concentrations correlated well with pigment levels present in food. Pigment contents in the hepatopancreas also showed some significant individual variations.

Lucien-Brun, Concentration of carotenoids in the tissues of sampled shrimp, Table 2

| No. Shrimp | Q (µg) | C (µg/g) |

|---|

No. Shrimp | Q (µg) | C (µg/g) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shrimp Shell | |||

| Diet T (0% alfalfa conc.) | 5 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 18.7 ± 10.8 |

| Diet A (4% alfalfa conc.) | 6 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 12.2 ± 2.3 |

| Diet B (8% alfalfa conc.) | 6 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 20.8 ± 10.7 |

| P (Farmed shrimp) | 6 | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 13.9 ± 6.3 |

| Shrimp Epidermis | |||

| Diet T (0% alfalfa conc.) | 5 | 24.8 ± 2.6 | 510 ± 141 |

| Diet A (4% alfalfa conc.) | 6 | 32.8 ± 12.1 | 890 ± 221 |

| Diet B (8% alfalfa conc.) | 6 | 42.2 ± 4.8 | 1,383 ± 318 |

| P (Farmed shrimp) | 6 | 27.8 ± 9.9 | 781 ± 235 |

| Shrimp Hepatopancreas | |||

| Diet T (0% alfalfa conc.) | 6 | 18.0 ± 10.0 | 28 ± 15 |

| Diet A (4% alfalfa conc.) | 6 | 81.0 ± 66.0 | 119 ± 95 |

| Diet B (8% alfalfa conc.) | 6 | 104.0 ± 78.0 | 156 ± 115 |

| P (Farmed shrimp) | 6 | 340.0 ± 90.0 | 1,144 ± 520 |

Lucien-Brun, Distribution of astaxanthin in the hepatopancreas and epidermis, Table 3

| Diet T (0% alfalfa conc.) | Diet A (4% alfalfa conc.) | Diet B (8% alfalfa conc.) |

|---|

Diet T (0% alfalfa conc.) | Diet A (4% alfalfa conc.) | Diet B (8% alfalfa conc.) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatopancreas | |||

| Free astaxanthin | 43.9% | 31.9% | 29.4% |

| Monoester astaxanthin | 8.7% | 24.8% | 24.0% |

| Diester astaxanthin | 12.0% | 15.0% | 18.0% |

| Total astaxanthin | 64.6% | 71.7% | 71.4% |

| Epidermis | |||

| Free astaxanthin | 48.4% | 55.3% | 48.5% |

| Monoester astaxanthin | 17.1% | 18.6% | 26.4% |

| Diester astaxanthin | 18.4% | 12.3% | 10.9% |

| Total astaxanthin | 83.9% | 86.2% | 85.8% |

Results also showed that the cultured blue shrimp fed pellets supplemented with alfalfa concentrate absorbed the pigment in the feed well. These shrimp showed higher pigment concentrations than those of the pond-raised shrimp.

(Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the April/May 2006 print edition of the Global Aquaculture Advocate.)

Now that you've finished reading the article ...

… we hope you’ll consider supporting our mission to document the evolution of the global aquaculture industry and share our vast network of contributors’ expansive knowledge every week.

By becoming a Global Seafood Alliance member, you’re ensuring that all of the pre-competitive work we do through member benefits, resources and events can continue. Individual membership costs just $50 a year. GSA individual and corporate members receive complimentary access to a series of GOAL virtual events beginning in April. Join now.

Not a GSA member? Join us.

Authors

-

-

Frederic Vidal

Aqua Techna

Les Landes de Bauche

BP 10

F-44220 Couëron, France

Tagged With

Related Posts

Health & Welfare

Diets for pond-raised red claw crayfish

Red claw crayfish have numerous attributes that make the species a good choice for aquaculture, including flexibility in feeding that may allow expensive prepared diets to be supplemented or replaced by natural foods or forages.

Health & Welfare

ELISA kits offer quantitative analysis of trifluralin in fish

Antibody-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) tests are proven, sensitive, high-throughput alternatives to more costly and complex test methods for the detection of herbicide residues and other chemicals.

Responsibility

Greenhouse-enclosed superintensive shrimp production

As an alternative to pond production, U.S. scientists have developed bio-secure greenhouse-enclosed raceways for intensive shrimp production with limited water exchange.

Innovation & Investment

Developments in closed-containment technologies for salmonids, part 1

The recent 2017 Aquaculture Innovation Workshop in Vancouver brought together numerous stakeholders involved in and interested in fish farming – particularly salmonids – in the growing industry of closed-containment systems.